Geometrical Neuroscience Laboratory

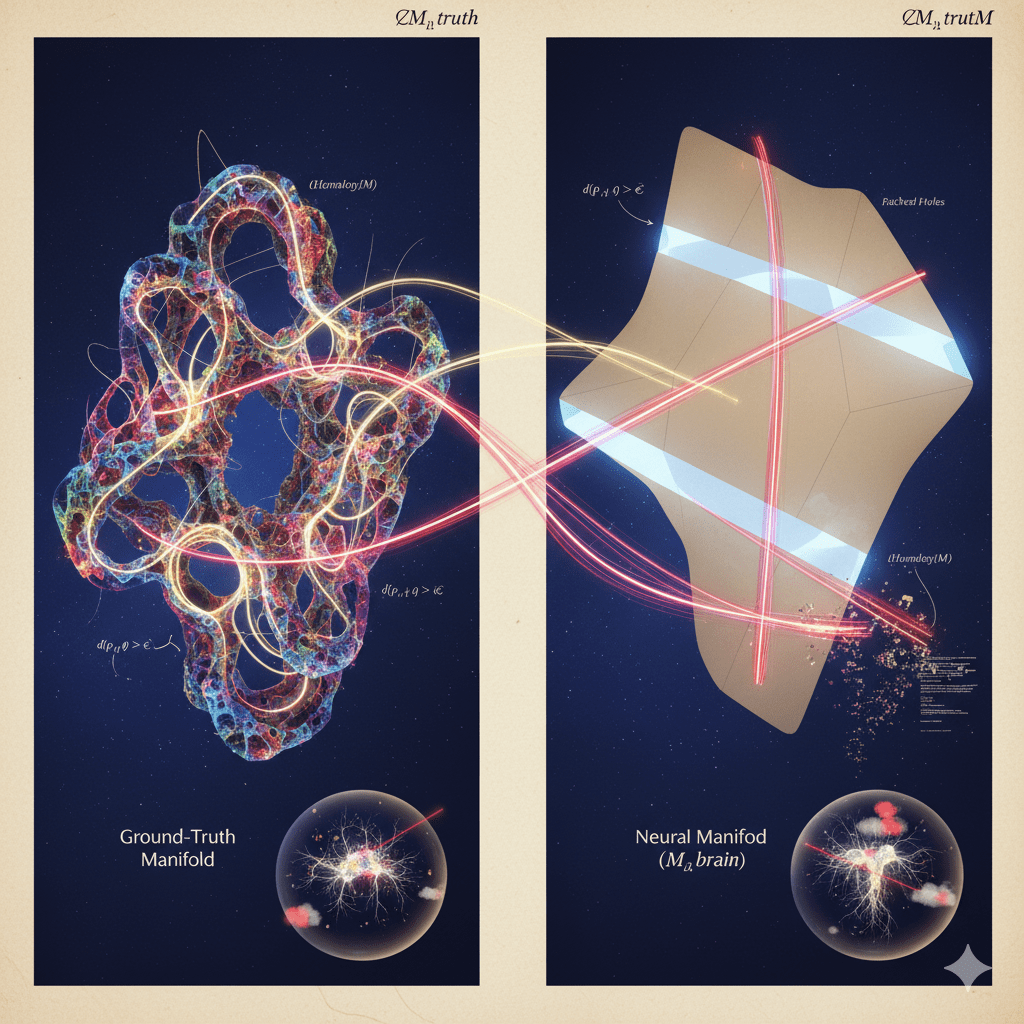

Mapping the Curvature, Topology, and Dynamics of Neural Function

Mission: Geometry as the Language of Neural Organization

The Geometrical Neuroscience Laboratory investigates the brain as a geometric system. We study how neural architecture embodies curvature, topology, and information flow. We treat neural organization not as circuitry but as a metric object that evolves in time.

We begin from a strict claim: structure and function are isomorphic. The geometry of the system is the computation of the system. Thought, learning, and perception are expressed as transformations of that geometry. Our work tries to write those transformations down.

Posts

Research Axes

1. Curvature and Neural Integration

We model neural activity as trajectories on a manifold (M, g_t), where g_t is a time-varying metric that encodes similarity between neural population states.

Local curvature is treated as the control variable of cognition. High positive curvature implies strong integration and coherence. Negative curvature implies specialization and separation of modes. We measure Ricci and Fisher–Rao curvature on structural and functional networks to identify the geometric signature of cognition.

Goal: describe “intelligence” as a property of curvature organization.

2. Topological Plasticity

We treat learning as a topological event, not just a weight update.

We analyze neural systems as evolving topological objects. Learning creates and destroys global structures (loops, cavities, high-order motifs). We use persistent homology and topological data analysis to track Betti trajectories (changes in Betti numbers across time). We then link these transitions to developmental changes or task-induced reconfiguration.

Goal: show that behavioral phase shifts correspond to topological bifurcations.

3. Information Geometry and Predictive Processing

We reinterpret predictive processing as a curvature-regulation process.

Under this view, the system reduces prediction error by reshaping its own metric. Learning is not just updating activity on a fixed space. Learning updates the space.

We express this as a flow:

g_dot = - ∇ F[g]

The brain is modeled as a variational system that deforms its own geometry to minimize free energy.

In this framing: surprise is curvature; learning is curvature reduction.

Goal: make “active inference” mathematically geometric, not metaphorical.

4. Statistical and Analog Neural Coding

We reject the idea that the brain computes primarily in discrete symbols.

We treat neural population codes as continuous probability distributions equipped with Fisher information metrics. Computation is then geodesic flow in that information space. In practice this means that reasoning is implemented as smooth analog transformation on a statistical manifold.

Goal: formalize analog intelligence and make it mechanically testable.

5. Morphogenetic Compute and Neuromorphic Realization

We build physical systems that obey these geometric laws.

On FPGA boards and Jetson Orin platforms we implement curvature-regularized, metric-adaptive systems. The objective is not to approximate biology. The objective is to create an isomorphic substrate: hardware whose physical update laws match the geometric laws we write.

Goal: show that curvature-driven learning can run in matter.

Mathematical Foundations of Geometric Neural Dynamics

This section makes explicit the equations and assumptions the lab treats as primary.

1. Coupled Flow Dynamics

The core geometric evolution law we study is:

∂t g_ij = -2 ( R_ij + λ I_ij )

Definitions:

g_ij(t)

The neural manifold metric at time t. It encodes which neural states are "close" or "far" in functional terms.

R_ij

The Ricci curvature tensor of that manifold. This term smooths and regularizes the geometry. It enforces internal coherence.

I_ij

The information-geometric term. We define I_ij as the Fisher information metric:

I_ij = E[ (∂ log p(x|θ) / ∂θ_i) * (∂ log p(x|θ) / ∂θ_j) ]

I_ij measures statistical sensitivity.

It favors encodings that are efficient, discriminative, and low-redundancy.

λ

A coupling constant. It controls how strongly information-theoretic pressure (I_ij) influences geometric reconfiguration relative to intrinsic curvature (R_ij).

Interpretation:

R_ijis homeostatic. It pushes the manifold toward smooth, globally consistent organization.I_ijis adaptive. It pushes the manifold toward statistically efficient codes.λbalances stability vs adaptation.

So the lab studies the brain as a system whose internal geometry flows under a joint Ricci–Fisher influence. Biology is modeled as a curvature flow.

Technical mapping note:

The Fisher metric I_ij is defined in information space (parameters θ of an internal model). We project that onto neural state space via a pullback. In other words, we map how informational efficiency pressures act back on the physical manifold (M, g_t).

2. Variational Free Energy Functional

We make “free energy minimization” explicit as a geometric descent.

We define a functional over the metric g:

F[g] = ∫_M [ R(g) + λ * D_KL( p_brain || p_world ) ] dμ_g

Definitions:

R(g)

The scalar curvature of the neural manifold. High R(g) reflects geometric stress.

D_KL( p_brain || p_world )

The divergence between the brain’s internal generative model and the actual

sampled environment. This is model-data mismatch, i.e. surprise.

dμ_g

The volume element induced by g. This makes F[g] depend on the geometry itself.

Then we define the update law:

g_dot = - ∇ F[g]

Meaning:

- The brain changes its own geometry

gto reduce two things:- internal geometric distortion (

R(g)), - model–world mismatch (

D_KL).

- internal geometric distortion (

- The manifold relaxes toward a state that is both smoother and better aligned with reality.

This gives a concrete reading for predictive coding:

the system is not just updating beliefs, it is literally reshaping its state space to make prediction cheaper.

3. Structure–Function Isomorphism

The lab uses “structure and function are isomorphic” in a strict technical sense.

We define a correspondence between two levels:

Connectome / network structure

→ Neural dynamical system on a manifold

Formally:

F : Graph_conn → DynSys_neural

Interpretation:

Graph_conn

Objects are structural or functional graphs (connectomes).

Morphisms are allowable rewiring operations.

DynSys_neural

Objects are dynamical systems evolving on manifolds with metrics g_t.

Morphisms are geometric flows that preserve key invariants.

F

Preserves invariants such as homology class (Betti structure) and curvature

profile. That is:

F( H_k(G) ) ≅ H_k( Φ_t(G) )

where H_k is the k-th homology group, and Φ_t is the corresponding neural flow.

Meaning:

- A change in structural topology is mirrored by a change in functional dynamics.

- Functional reconfiguration (how the system processes information) can be read back into structural terms.

- “Surprise is curvature; learning is curvature reduction” becomes literal:

d/dt D_KL( p_brain || p_world ) < 0

⇔

local curvature in information space is being flattened

⇔

the system is aligning function with structure

So the isomorphism claim is not poetic. It is a claim of categorical preservation: topology ↔ dynamics.

Hypothesis-Driven Research Programs

We present these as explicit hypotheses rather than topics.

1. Curvature of the Connectome

Hypothesis:

Hyperbolic (negatively curved) regions of the connectome, quantified using Ollivier–Ricci curvature, are positively associated with fluid intelligence.

Reasoning: negative curvature supports efficient specialization and segregated parallel processing.

Method:

Estimate local curvature on structural and functional graphs (HCP, ABCD). Regress curvature features against cognitive efficiency measures.

2. Predictive Morphogenesis

Hypothesis:

A neural field governed by:

g_dot = - ∇ F[g]

will self-organize into steady-state curvature profiles that match empirical connectome curvature distributions.

Method:

Simulate Ricci–Fisher flows using empirical priors. Compare the emergent curvature spectra to measured human data. If matched, geometry is sufficient to generate observed integration patterns.

3. Hybrid Morphogenetic Compute Platform

Hypothesis:

Curvature-regularized FPGA and Jetson Orin systems will display convergence dynamics analogous to biological learning trajectories.

Method:

Implement the coupled flow:

∂t g_ij = -2 ( R_ij + λ I_ij )

in reconfigurable hardware. Measure whether the system lowers an energy functional equivalent to F[g] over time. This tests physical realizability.

4. Ricci–Fisher Developmental Flow

Hypothesis:

Developmental changes in cognitive integration are driven by Ricci–Fisher curvature transitions across scales (structural → functional → symbolic).

Method:

Fit curvature parameters to longitudinal developmental neuroimaging and behavioral calibration data. Relate manifold smoothing and curvature reallocation to developmental stage shifts.

5. Topological Reconfiguration in Task Networks

Hypothesis:

Behavioral phase transitions under cognitive load correspond to bifurcations in Betti structure (appearance/disappearance of topological features in functional connectivity over time).

Method:

Use persistent homology to track Betti numbers across rapid task-switching. Link topological breakpoints to performance collapse or control recovery.

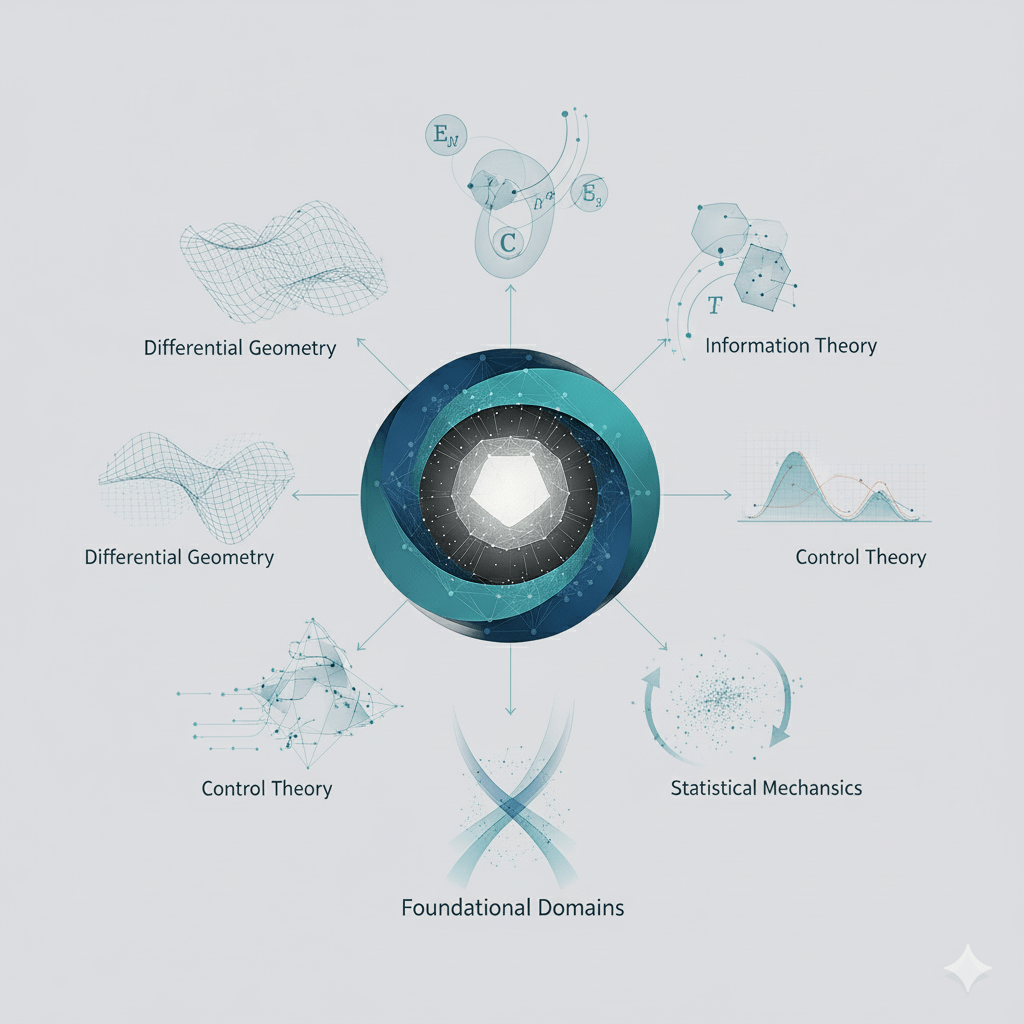

Foundational Domains

Differential Geometry

Neural dynamics are modeled as curvature flow.

Topology

Learning is modeled as homological transition.

Information Theory

Entropy–curvature duality links model uncertainty to geometric deformation.

Control Theory

Homeostasis is modeled as curvature stabilization under feedback control.

Statistical Mechanics

The brain is modeled as a nonequilibrium field system under continuous energy minimization.

Vision

The aim of the Geometrical Neuroscience Laboratory is direct.

We want the laws of neural geometry.

We want to show that curvature, prediction, and adaptation are the same process.

We want to prove that intelligence is a geometric engine that can be written, analyzed, and built.

Bibliography

1. Differential and Information Geometry in Neural Systems

- Amari, S. (2016). Information Geometry and Its Applications. Springer.

- Amari, S., & Nagaoka, H. (2000). Methods of Information Geometry. American Mathematical Society.

- Penrose, R. (2004). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Jonathan Cape.

- Chentsov, N. N. (1982). Statistical Decision Rules and Optimal Inference. American Mathematical Society.

- Nielsen, F., & Garcia, V. (2013). “Statistical exponential families: A digest with flash cards.” arXiv:0911.4863.

- Eells, J., & Sampson, J. H. (1964). “Harmonic mappings of Riemannian manifolds.” American Journal of Mathematics, 86(1), 109–160.

- Perelman, G. (2002). “The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications.” arXiv:math/0211159.

- Hamilton, R. S. (1982). “Three-manifolds with positive Ricci curvature.” Journal of Differential Geometry, 17(2), 255–306.

- Yano, K., & Ishihara, S. (1973). Tangent and Cotangent Bundles: Differential Geometry. Marcel Dekker.

2. Predictive Processing and Variational Free Energy

- Friston, K. (2010). “The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

- Friston, K., Kilner, J., & Harrison, L. (2006). “A free energy principle for the brain.” Journal of Physiology – Paris, 100(1–3), 70–87.

- Parr, T., Pezzulo, G., & Friston, K. J. (2022). Active Inference: The Free Energy Principle in Mind, Brain, and Behavior. MIT Press.

- Clark, A. (2016). Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind. Oxford University Press.

- Hohwy, J. (2013). The Predictive Mind. Oxford University Press.

- Bogacz, R. (2017). “A tutorial on the free-energy framework for modelling perception and learning.” Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 76, 198–211.

- Buckley, C. L., Kim, C. S., McGregor, S., & Seth, A. K. (2017). “The free energy principle for action and perception: A mathematical review.” Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 81, 55–79.

3. Topological and Network Approaches

- Giusti, C., Ghrist, R., & Bassett, D. S. (2016). “Two’s company, three (or more) is a simplex: Algebraic-topological tools for understanding higher-order structure in neural data.” Journal of Computational Neuroscience, 41, 1–14.

- Petri, G., & Expert, P. (2020). “Topological data analysis of complex networks: An emerging field.” IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering, 7(2), 843–859.

- Sizemore, A. E., Giusti, C., & Bassett, D. S. (2018). “Classification of weighted networks through mesoscale homological features.” Journal of Complex Networks, 6(2), 245–273.

- Stolz, B. J. (2021). “Introduction to persistent homology for neuroscience.” Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, 15, 703281.

- Sporns, O. (2011). Networks of the Brain. MIT Press.

- Petri, G., et al. (2014). “Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks.” Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 11(101), 20140873.

4. Statistical and Analog Neural Coding

- Seung, H. S. (1996). “How the brain keeps the eyes still.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(23), 13339–13344.

- Pouget, A., Dayan, P., & Zemel, R. S. (2003). “Inference and computation with population codes.” Annual Review of Neuroscience, 26(1), 381–410.

- Beck, J. M., Ma, W. J., Pitkow, X., Latham, P. E., & Pouget, A. (2012). “Not noisy, just wrong: The role of suboptimal inference in behavioral variability.” Neuron, 74(1), 30–39.

- Eliasmith, C. (2005). Neurosemantics and Symbol Grounding. MIT Press.

- Denève, S., & Machens, C. K. (2016). “Efficient codes and balanced networks.” Nature Neuroscience, 19(3), 375–382.

- Olshausen, B. A., & Field, D. J. (1996). “Emergence of simple-cell receptive field properties by learning a sparse code for natural images.” Nature, 381(6583), 607–609.

5. Morphogenetic Compute and Neuromorphic Realization

- Mead, C. (1990). “Neuromorphic electronic systems.” Proceedings of the IEEE, 78(10), 1629–1636.

- Furber, S. (2016). “Large-scale neuromorphic computing systems.” Journal of Neural Engineering, 13(5), 051001.

- Indiveri, G., & Liu, S.-C. (2015). “Memory and information processing in neuromorphic systems.” Proceedings of the IEEE, 103(8), 1379–1397.

- Davies, M., et al. (2018). “Loihi: A neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning.” IEEE Micro, 38(1), 82–99.

- Roy, K., Jaiswal, A., & Panda, P. (2019). “Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing.” Nature, 575(7784), 607–617.

- Doya, K. (2021). “Computational neuroscience: From biological models to brain-inspired architectures.” Nature Neuroscience, 24(8), 1139–1149.

6. Developmental and Morphogenetic Frameworks

- Demetriou, A., Spanoudis, G., & Shayer, M. (2017). “Cognitive development from adolescence to mid-adulthood: Structural models of processes, mechanisms, and speed.” Intelligence, 61, 84–95.

- Edelman, G. M. (1987). Neural Darwinism: The Theory of Neuronal Group Selection. Basic Books.

- Changeux, J.-P., & Dehaene, S. (1989). “Neuronal models of cognitive functions.” Cognition, 33(1–2), 63–109.

- Kelso, J. A. S. (1995). Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior. MIT Press.

- Sporns, O., Tononi, G., & Kötter, R. (2005). “The human connectome: A structural description of the human brain.” PLoS Computational Biology, 1(4), e42.

7. Conceptual and Philosophical Foundations

- Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and Repetition. Columbia University Press.

- Thom, R. (1972). Structural Stability and Morphogenesis. W. A. Benjamin.

- Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Dutton.

- Rosen, R. (1991). Life Itself: A Comprehensive Inquiry into the Nature, Origin, and Fabrication of Life. Columbia University Press.

- Smolensky, P. (1988). “On the proper treatment of connectionism.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 11(1), 1–23.

- Churchland, P. S., & Sejnowski, T. J. (1992). The Computational Brain. MIT Press.