Attractiveness is frequently miscategorized as a static physical trait (geometry) or a vague psychological quality (“confidence”). Both definitions fail to account for the non-linear dynamics of social interaction. Specifically, they fail to explain the common phenomenon where a subjective “unlocking” of self-worth leads to an immediate, discontinuous jump in external social feedback, independent of significant physical changes.

This article proposes a mechanistic framework for this phenomenon. We posit that a sudden increase in social attractiveness constitutes a topological phase transition in the agent’s generative self-model. This internal reconfiguration propagates outward through two specific channels: active inference (which alters embodied motor policies) and signaling equilibria (which coordinate observer responses).

By integrating predictive processing neuroscience, Bayesian social perception, and game theory, we can operationalize the “glow up” not as magic, but as a lawful stabilization of a complex system. This framework is particularly critical for developing minds (adolescents and young adults), where the calibration of social priors is most volatile and the risk of permanent “low-status” equilibrium fixation is highest.

The Problem of Static Attractiveness Models

The prevailing folk-psychological model of attractiveness is linear and additive. It assumes that an individual’s Social Value (V) is the sum of physical features (P) and behavioral traits (B). Under this view, increasing V requires a slow, incremental increase in P or B.

However, this linear model fails to predict the step-function changes observed in social dynamics. Individuals often report prolonged periods of stagnation followed by sudden shifts in social receptivity after an internal cognitive reframing.

Furthermore, the advice to “fake it until you make it” creates a paradox of dissonance. From a signal processing perspective, “faking” creates high-entropy noise. When an agent attempts to enact a high-status behavior (B-high) while maintaining a low-status internal prior (P-low), the system generates prediction error. This error leaks out as micro-kinematic jitter—fidgeting, vocal tremors, and discordant affect—which observers subconsciously decode as inauthenticity or threat [CITE: Literature on nonverbal leakage/deception detection].

We need a model that explains how an internal update eliminates this noise, creating a coherent signal that triggers a new social equilibrium.

Theory Part I: The Neuroscience of the Self-Model

To understand the phase transition, we must first formalize the “self” using the Free Energy Principle and Predictive Processing [CITE: Friston, 2010; Clark, 2013].

High-Level Priors and Identity States

The brain functions as a hierarchical generative model. It minimizes “surprisal” by predicting incoming sensory data based on high-level priors. The “Self” is not a homunculus, but a probability distribution over hidden states.

Let the agent’s identity state space be S. The agent holds a prior probability distribution P(s) over these states, where s can be unattractive, neutral, or attractive.

For the “unlocked” agent, the prior shifts. It is not merely that they “think” they are attractive; the probability density function of their identity shifts its mode.

P(s = attractive) ≈ 1

This is not a superficial thought; it is a deep temporal prior. It constrains how the brain predicts interoceptive (internal body) and exteroceptive (external social) signals. If the deep prior is strong, the brain treats contrary evidence (e.g., a rejection) as noise rather than a signal to update the model, maintaining stability [CITE: Research on precision weighting in predictive coding].

The Topology of Phase Transitions

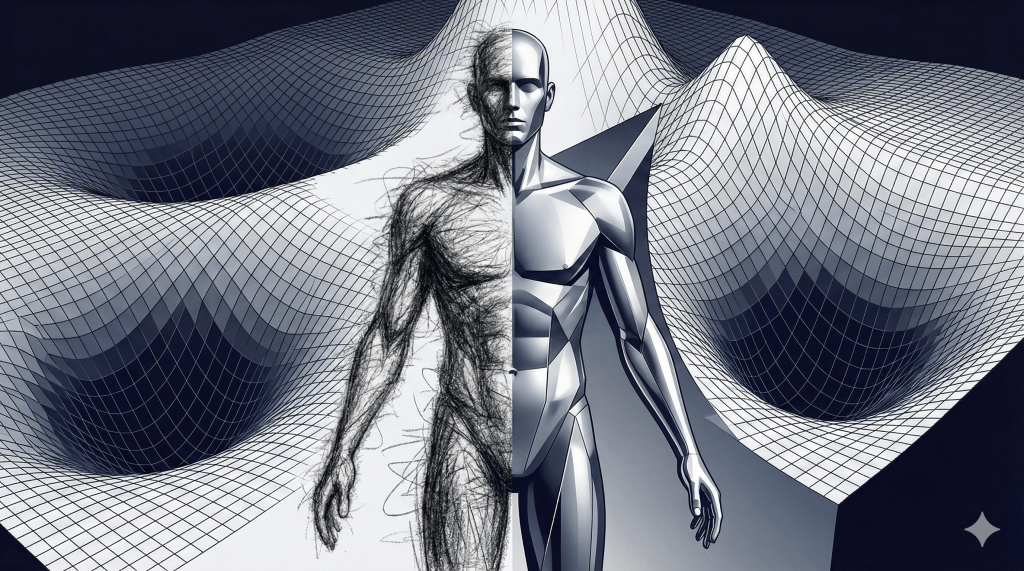

We describe the shift not as a scalar increase in self-esteem, but as a topological phase transition in the manifold of the self-model.

Imagine the self-model as an energy landscape (a potential function).

- State A (The Inhibited Self): A deep valley (attractor basin) representing low status and risk aversion. Escaping this valley is energetically costly due to shame or fear of social punishment.

- State B (The Attractive Self): A separate attractor basin representing high status and expression.

In a phase transition, the parameter controlling the landscape (the “control parameter,” often subjective permission or trauma resolution) changes. The barrier between State A and State B collapses. The system creates a new global minimum. The agent does not “climb” out of low self-esteem; the landscape itself tilts, and the agent “falls” into the attractive state. This explains the suddenness and ease of the behavioral change once the internal shift occurs

Theory Part II: Embodied Implementation (The Mechanism)

How does a mental prior change physical reality? Through Active Inference.

In the Active Inference framework, the brain minimizes prediction error in two ways:

- Perception: Updating internal beliefs to match sensory inputs.

- Action: Moving the body to make sensory inputs match internal predictions.

When the prior shifts to P(s = attractive), the brain predicts sensory data consistent with that state: a calm heart rate, an erect posture, and a resonant voice. If the current physical state is slumped and anxious, the brain registers a proprioceptive prediction error.

To resolve this, the motor cortex and autonomic systems execute a new policy (π) to align the body with the belief.

Motor Policy Recalibration

The motor system, specifically the corticospinal tracts and cerebellum, receives top-down predictions of “high-status kinematics.”

- Posture: The thoracic cage expands, and the head stabilizes. This is not “posturing”; it is the body fulfilling a prediction of verticality and openness.

- Gaze: The prior for “high status” predicts a stable visual field. Micro-saccades (jittery eye movements) are suppressed [CITE: Research on gaze dominance and status].

- Movement: The velocity profiles of limb movements become smoother (minimizing jerk), as the system is no longer predicting a need for rapid flight responses.

Autonomic and Affective Regulation

The most critical signal of attractiveness is autonomic balance. The “Unattractive” prior often predicts social threat, activating the sympathetic nervous system (fight/flight). This results in dilated pupils, sweating, and vocal cord tension.

The “Attractive” prior predicts social safety or dominance. This engages the ventral vagal complex (parasympathetic system), associated with social engagement [CITE: Porges, Polyvagal Theory].

- Vocal Prosody: Vagal activation relaxes the laryngeal muscles, lowering fundamental frequency (F0) and increasing resonance—a universal attractiveness cue.

- Facial Dynamics: Reduced sympathetic tone eliminates micro-tremors in the facial muscles, leading to what observers perceive as “composure.”

Special Case: The Adolescent and Young Adult Critical Period

The dynamics described above are intensified during adolescence and early adulthood (ages 15–25) due to neurodevelopmental plasticity. This demographic represents a “high-volatility” market where priors are unsolidified, and social signaling carries maximal evolutionary weight.

Synaptic Pruning and Prior Instability

During this window, the brain undergoes significant synaptic pruning, particularly in the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) which governs social cognition and self-regulation. Consequently, the “Self-Model” (P(s)) is highly plastic.

In adults, priors are rigid (low variance). In young adults, priors are susceptible to rapid updating based on social prediction error.

Update Sensitivity ∝ 1 / Prior Precision

Because the “Self” prior has low precision in youth, external feedback (e.g., “cringe” or validation) causes massive swings in the self-model. This explains the extreme binary nature of young adult social status: one is either “the main character” or “invisible,” with rapid oscillations between states. The phase transition we describe is, therefore, most accessible—and most dangerous—during this period.

“The Ick” as a Bayesian Rejection of Incongruence

The slang term “The Ick,” popular among Gen Z, is a precise linguistic marker for the detection of signal incongruence. It describes a sudden, irreversible loss of attraction triggered by a specific behavior.

Mechanistically, “The Ick” occurs when an observer detects a mismatch between an agent’s explicit signaling (bravado/attempted coolness) and their implicit leakage (micro-tremors/awkwardness).

Ick = Detect( | Explicit Signal – Implicit Leakage | > Threshold )

For young adults, whose peers are hyper-vigilant to inauthenticity, the “fake it till you make it” strategy is fatal. The only viable strategy is the genuine topological shift of the self-model, which eliminates the leakage entirely.

Evidence: The Observer’s Inference Engine

The agent has updated their signals. How does the observer process them? We model the observer as a Bayesian Decoder solving an inverse problem.

The Inverse Problem

The observer receives a stream of noisy sensory data (D): kinematics, vocal tone, grooming, and eye contact. They must infer the latent variable (Z): the agent’s mate value or social status.

P(Z | D) ∝ P(D | Z)P(Z)

- P(Z): The observer’s prior belief about the distribution of attractiveness in the population.

- P(D | Z): The likelihood function. How probable is this specific behavior (D) given that the person is attractive (Z)?

Thin-Slicing and Coherence

Research on “thin-slice” judgments confirms that humans assess traits like dominance, competence, and trustworthiness within 50 to 500 milliseconds [CITE: Ambady & Rosenthal, 1992; Willis & Todorov, 2006].

Crucially, observers value signal coherence (low entropy).

- Incoherent Signal: A person trying to “act” attractive might have good posture but a shaky voice. The observer detects the variance: D does not fit the cluster for Z-high. The inference defaults to Z-deceptive or Z-anxious.

- Coherent Signal: The “phase-shifted” agent presents a unified front. Posture, voice, and micro-expressions all align. The likelihood P(D | Z-high) spikes.

Because the observer’s inference is rapid and largely subconscious, the feedback they give (interest, respect, attraction) changes the moment the agent’s signal coherence improves.

Synthesis: Game-Theoretic Equilibrium Selection

Finally, we move from the individual dyad to the group dynamic. Attractiveness is not just a biological trait; it is a Game-Theoretic Equilibrium.

Signaling and Coordination

In a mating or status market, participants are playing a coordination game with imperfect information. Observers are looking for “Schelling points”—focal points of value that others also recognize.

- Equilibrium 1 (The Invisible Agent): The agent signals low value. The group coordinates around ignoring the agent. Deviating from this strategy (e.g., one person showing interest) carries social risk.

- Equilibrium 2 (The Attractive Agent): The agent signals high value. The group coordinates around competing for or aligning with the agent.

Digital Extensions of the Equilibrium (The “Profile” Dynamic)

For modern cohorts (Gen Z/Alpha), this coordination game is played asynchronously via digital proxies (Instagram, TikTok). The “Profile” functions as an externalized generative model.

However, a dangerous dissonance often emerges here.

- Digital Inflation: The agent curates a profile where P-digital(s) = high.

- Physical Deflation: The agent’s embodied reality remains P-physical(s) = low.

When these two models collide in real-time interaction, the Divergence Error is catastrophic.

E-divergence = || Digital Persona – Physical Presence ||

If E-divergence is high, the observer feels “catfished”—not necessarily physically, but energetically. The phase transition described in this paper requires that the embodied self updates first. When the physical self-model shifts, the digital extension becomes a natural byproduct (“dump” aesthetic) rather than a desperate curation, which paradoxically signals higher status.

The Feedback Loop

The “unlock” triggers a transition between these equilibria.

- Internal Phase Shift: Agent updates prior P(s).

- Signal Fidelity: Active inference generates coherent high-value signals (D).

- Observer Update: A subset of observers (early adopters) updates their posterior P(Z | D).

- Social Proof: The attention from early adopters serves as a new public signal for the rest of the group.

- New Equilibrium: The system settles into Equilibrium 2, where the agent is universally treated as attractive.

[FIGURE: A payoff matrix or flow diagram showing the shift from a low-attention equilibrium to a high-attention equilibrium. Caption: Social attention follows a ‘winner-take-all’ dynamic, stabilizing around clear signals of value. Source: Modeled on signaling game dynamics. Takeaway: Coherent signaling reduces the risk for observers to invest attention.]

Implications

The theoretical model presented here—connecting Generative Models, Active Inference, and Game Theory—has significant practical implications.

For Self-Development

Standard advice focuses on behavioral scripts (“stand up straight,” “say this line”). This model suggests that behavioral scripts are computationally expensive and prone to leakage. The most efficient intervention is at the level of the generative prior. Techniques that alter the deep self-model (e.g., trauma processing, identity shifting, visualization that targets motor imagery) are mechanistically superior to “fake it till you make it” strategies.

[INTERNAL_LINK: Identity Shifting Protocols -> identity-shifting-protocols]

For Artificial Intelligence & Social Robotics

To create socially “attractive” or persuasive agents, developers cannot simply program polite scripts. Agents must possess a hierarchical goal structure where “social confidence” is a high-level prior that drives consistent, low-entropy outputs across all modalities (text, voice, avatar movement).

Conclusion

The phenomenon of becoming attractive “overnight” following an internal realization is not a placebo effect. It is a mechanistic propagation of a high-level prior through the levels of a hierarchical system.

- Neuroscience: The self-model undergoes a topological phase transition, creating a new attractor basin for identity.

- Embodiment: Active inference minimizes the error between this new identity and the physical body, regulating posture and autonomic tone.

- Interaction: Observers decode this coherent low-entropy signal using Bayesian inference.

- Dynamics: The social group re-equilibrates around this new signal.

By understanding attractiveness as a distributed inference problem rather than a static attribute, we regain agency over the process. The “Unlock” is simply the moment the system finds a new, more stable energy minimum.

End Matter

Assumptions

- Predictive Processing Validity: This model assumes the brain operates according to the Free Energy Principle (Friston et al.).

- Observer Rationality: We assume observers act as boundedly rational Bayesian updaters who prioritize signal coherence.

- Signal Honesty: We assume that while short-term deception is possible, long-term maintenance of high-status signals without internal congruence is metabolically prohibitive (the Handicap Principle).

Limits

- Physical Constraints: No amount of internal priors can overcome severe physical deformities or health markers that signal genetic incompatibility. The model modulates perceived value within the agent’s phenotypic range.

- Cultural Variance: The specific cues for Z-high (e.g., eye contact duration, vocal volume) vary by culture, though the underlying requirement for signal coherence is universal.

- Developmental Variation: The speed of the phase transition is faster in adolescents (high plasticity) but the risk of reversion is also higher compared to older adults (low plasticity, high stability).

Testable Predictions

- Physiological: Subjects who undergo a successful “mindset intervention” will show measurable increases in Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and decreases in voice fundamental frequency (F0) variance within 10 days.

- Kinematic: Motion capture analysis will reveal a reduction in micro-saccade frequency and postural sway (center of pressure velocity) post-transition.

- Social: In speed-dating scenarios, subjects with high “internal coherence” (measured by congruency between self-report and physiological state) will receive higher attractiveness ratings than subjects with objectively better physical features but lower coherence.

- Digital: Analysis of social media metrics will show that “low effort” posts from high-coherence users generate higher engagement than “high effort” curation from low-coherence users, validating the signal leakage hypothesis in digital media.

References

[1] Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127-138. [2] Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181-204. [3] Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116-143. [4] Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R. (1992). Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 256. [5] Willis, J., & Todorov, A. (2006). First impressions: Making up your mind after a 100-ms exposure to a face. Psychological Science, 17(7), 592-598. [6] Pentland, A. (2010). To signal is human: Real-time data mining looks for the ‘honest signals’ that predict human behavior. American Scientist, 98(3), 204-211. [7] Schelling, T. C. (1960). The Strategy of Conflict. Harvard University Press. [8] Zahavi, A. (1975). Mate selection—a selection for a handicap. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 53(1), 205-214. [9] Seth, A. K. (2013). Interoceptive inference, emotion, and the embodied self. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(11), 565-573. [10] Cuddy, A. J., Wilmuth, C. A., & Carney, D. R. (2015). The benefit of power posing before a high-stakes social evaluation. Harvard Business School Working Paper, 13-027. [11] Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355-374. [12] Blakemore, S. J. (2008). The social brain in adolescence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(4), 267-277. [13] Crone, E. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(9), 636-650. [14] Turkle, S. (2011). Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books. [15] Maynard Smith, J. (1982). Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge University Press.