H2: Introduction

H3: The Classical View of Desire: Energy and Displacement

The history of psychoanalysis is, in many respects, the history of attempting to formalize human desire. Sigmund Freud’s original “economic” model presented a quantitative framework: psychic energy (libido), finding itself blocked by repression, builds “pressure” and must be displaced onto new objects (Freud, 1915a). This hydraulic metaphor, while powerful, treats libido as a simple, scalar quantity.

Jacques Lacan radically updated this framework, arguing that desire is not a biological drive but a symbolic function, “the desire of the Other” (Lacan, 1977). For Lacan, desire moves metonymically along a static “signifying chain,” a discrete graph of S…S′. While this structuralist approach correctly identifies desire as an effect of language, it struggles to account for dynamics, intensity, and continuous change. It provides the structure of the symbolic order but not the physics of the drive within it.

H3: The Topological Thesis: Desire as Dynamical Flow

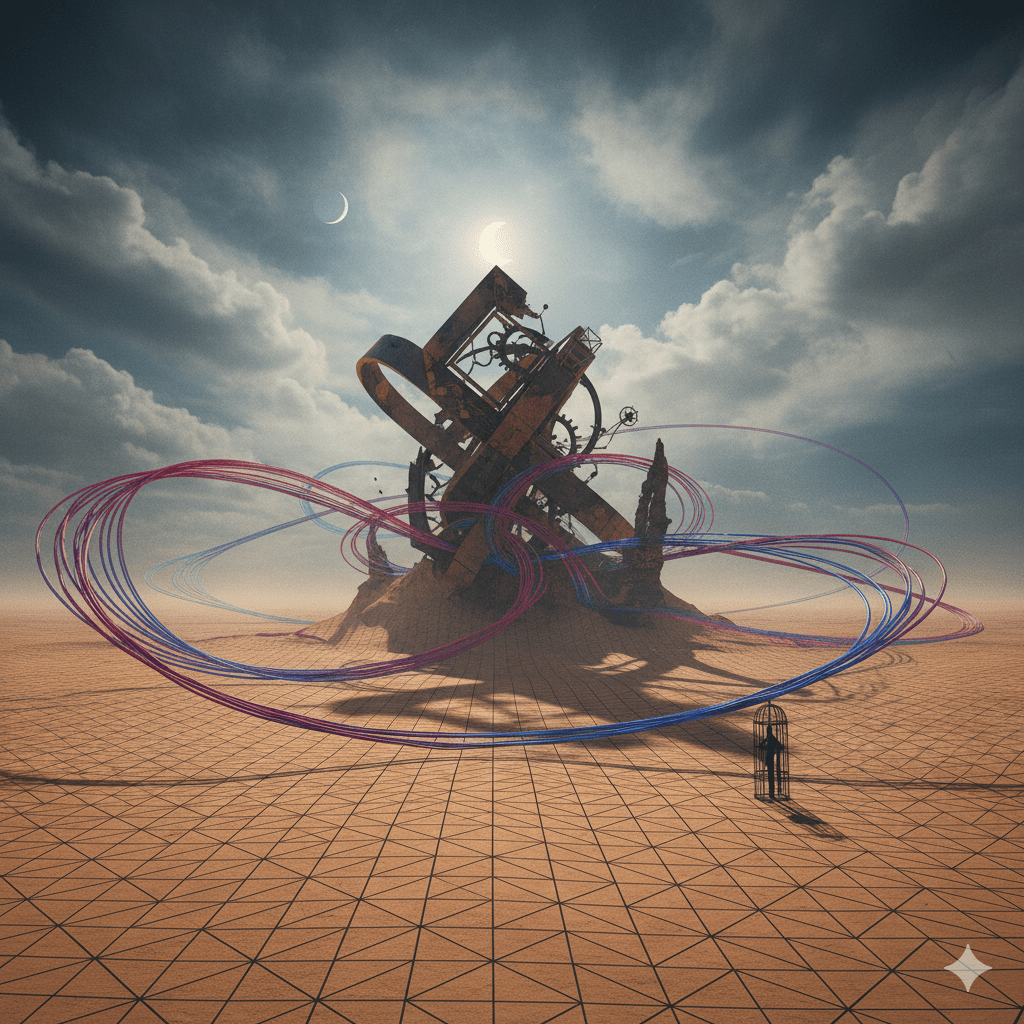

Both classical models—one of fluid dynamics, the other of static semiotics—are insufficient. They fail to capture the process of desire: its continuous flow, its capture in repetitive loops, and its variation in intensity. The “static graph” model of the signifying chain cannot adequately explain why desire flows to specific points (symptoms, fantasies) with such powerful, unyielding force.

This paper proposes a new thesis: desire is a dynamical flow operating on a geometric substrate. We posit that the symbolic order is not a discrete chain but a continuous, high-dimensional space—a manifold. The movement of libido is not a simple displacement but a vector field defined on this surface.

H3: Introducing the Libidinal Flow Model (LFM)

To formalize this thesis, we introduce the Libidinal Flow Model (LFM). The LFM is a dynamical-topological framework that unites Lacan’s structuralism with the formalisms of differential geometry and information theory (Amari, 2016).

The LFM is built on a central claim: Desire is a vector field defined over a symbolic manifold, with libidinal intensity acting as a potential field and the fundamental fantasy functioning as the manifold’s local curvature.

This model moves beyond metaphor by positing that the symbolic manifold is empirically discoverable within the geometric structure of semantic vector spaces. The LFM provides a rigorous language for describing how desire flows, why it gets “stuck,” and how the analytic process functions to restore its mobility.

H2: The Problem with Static Symbolic Models

H3: Limitations of Freudian Hydrodynamics

Freud’s economic model, while foundational, is operationally limited. It treats libido as an undifferentiated quantum of energy (Freud, 1915a). This “hydrodynamic” view explains the pressure of the drive (e.g., symptom formation as a “return of the repressed”) but cannot describe the intricate, specific pathways that desire takes. It lacks directionality. A simple pressure gradient is insufficient to explain the complex, over-determined structure of a fantasy or a symptom, which seems to follow a specific, repeating logical pattern.

H3: Lacan’s Static Signifiers: A Need for Dynamics

Lacan’s great advance was to link desire to the structure of language (Lacan, 1977). The subject is “barred” ($) by their entry into the symbolic, and desire is the metonymic gap between signifiers (S1→S2). However, the classical Lacanian “graph of desire” is topological in only a rudimentary, graph-theoretic sense. It describes connections (edges) between discrete points (nodes/signifiers).

This static topology cannot explain the intensive properties of desire. Why does one signifier (e.g., in a trauma) acquire a “charge” that warps the entire field? How does the “pull” of jouissance (painful pleasure) function as more than just another node in the graph, but as a “gravity well” that deforms all surrounding pathways? [INTERNAL_LINK: The signifier as a discrete unit -> /blog/what-is-a-signifier]. We need to move from a discrete graph to a continuous, differentiable surface.

H3: Defining Key Terms

To build the LFM, we must first define its components with rigor.

- Symbolic Manifold (Ms): We define the symbolic manifold as a high-dimensional differentiable manifold where each point corresponds to a symbolic element (a signifier or concept). “Differentiable” means the space is smooth and continuous, allowing us to use calculus. We operationally propose that Ms can be approximated by the geometric spaces derived from large-language models (e.g., semantic vector spaces), where proximity and relation are defined geometrically (Mikolov et al., 2013).

- Vector Field (D): A vector field on Ms assigns a vector (with both direction and magnitude) to every point on the manifold. We define desire, D

, as this vector field. It represents the “push” or “flow” of libido at any given symbolic location (Tu, 2011).

- Potential (Φ): A scalar field on Ms that assigns a single number (magnitude) to every point, representing libidinal “intensity” or “investment.”

H2: Theory: The Libidinal Flow Model (LFM)

The LFM rests on four postulates that describe the physics of desire on the symbolic manifold.

H3: Postulate 1: The Symbolic Field as a Differentiable Manifold

The set of all signifiers accessible to a subject does not form a discrete set, but a continuous, high-dimensional space, the Symbolic Manifold (Ms). Its differentiability is key: it means we can measure rates of change (derivatives) and curvature, moving from a “connect-the-dots” graph to a smooth landscape (Tu, 2011).

H3: Postulate 2: Libidinal Intensity as Potential (∇Φ)

Libidinal investment is not a static quantity but a scalar potential field, Φ(p), defined over all points p on Ms. This potential represents the psychic “pressure” or “charge” at that symbolic location. For example, a traumatic signifier would represent a point of extremely high potential.

H3: Postulate 3: Fantasy as Curvature (R)

This is the LFM’s central contribution. The fundamental fantasy is not an object or narrative but the intrinsic geometry of the symbolic manifold itself. We posit that the fantasy is encoded as the curvature tensor (R) of Ms.

A “flat” manifold (zero curvature) would represent a “healthy” or “perverse” (in the Deleuzian sense) subject, where libido flows freely. A pathologically “curved” manifold represents a neurotic or psychotic subject. Here, the geometry itself dictates the flow, forcing libido into non-obvious paths, loops, and traps. The fantasy, as curvature, is the law that governs desire’s movement (Savva, 2025).

H3: Postulate 4: Desire as a Vector Field (D![]() )

)

Desire, D, is the libidinal flow itself. In physics, flow is the natural response to a gradient in potential. Therefore, we define the desire vector field as the negative gradient of the libidinal potential:

D=−∇Φ

This equation formally unites the components. It states that desire (D) at any point flows “downhill” from high potential (Φ) to low potential, but its path is constrained by the geometry (curvature, R) of the manifold on which the gradient (∇) is calculated.

H2: Evidence and Examples

The LFM’s value lies in its power to re-describe classical psychoanalytic concepts in a formal, unified language.

H3: Topological Invariants: Repression as a Closed Loop

How does the LFM model repression? In this framework, repression is a topological feature of Ms. It is a region of the manifold that is “cut” and “re-glued,” creating a non-contractible loop or a “hole” (in algebraic topology, a non-trivial first homology group, H1(Ms)=0).

Desire (D) flowing near this loop cannot “cross” the repressed boundary. It is forced to flow around it, creating the repetitive, circling motion characteristic of symptoms that “speak” the truth of the repression without ever touching it (Hatcher, 2002). The symptom is the path of desire forced by this topological obstruction.

H3: Jouissance as an Attractor Basin

Jouissance, the paradoxical “painful pleasure” that lies “beyond the pleasure principle,” is also a geometric feature. In the LFM, jouissance is modeled as an attractor in the dynamical system defined by D (Strogatz, 2015).

It is a “basin of attraction”—a region of Ms (e.g., the objet petit a) where all nearby desire vectors D converge. This attractor is “pathological” because it acts as a sink, a “black hole” for libido, trapping it in a self-reinforcing, auto-erotic loop that provides intense (painful) charge but no symbolic resolution. [INTERNAL_LINK: Formalizing the ‘objet a’ -> /blog/lacan-objet-a].

H2: Objections and Counterarguments

H3: The Risk of Unoperationalized Metaphor

The most significant objection is that the LFM is merely a “metaphor on top of a metaphor.” Is “symbolic curvature” any more rigorous than Freud’s “psychic energy”?

We argue: yes, because it is operationalizable. The LFM proposes that Ms is not a pure abstraction but is empirically approximated by the high-dimensional manifolds of semantic vector spaces (word embeddings) (Devlin et al., 2019). The curvature of these semantic spaces is a measurable quantity (Amari, 2016). This provides a direct, empirical bridge from the psychoanalytic concept of “fantasy” to the geometric analysis of a subject’s language data.

H3: Reconciling with Neurobiology (Solms, 2023)

How does the LFM, a high-level symbolic model, map to the “wetware” of the brain? We do not propose a 1:1 mapping. Instead, we bridge LFM with affective neuroscience.

We follow Mark Solms (2021), who identifies the brainstem as the source of “free energy” or pure affect. In LFM terms, the brainstem provides the scalar potential (Φ). The cortex, with its complex associative networks, provides the manifold structure (Ms). The LFM thus models the interaction between brainstem energy and cortical structure. This aligns with Friston’s (2010) free-energy principle and the “entropic brain” hypothesis: a rigid, obsessive state (high curvature) is a low-entropy state, while psychosis (flat manifold) is a high-entropy state (Carhart-Harris, 2018). [INTERNAL_LINK: Affective neuroscience -> /pillar/neuroscience-of-affect].

H3: The Deleuzian Challenge: Flow vs. Structure (Deleuze & Guattari, 1980)

Deleuze and Guattari (1987) also spoke of “flows of desire” on a “body without organs.” How is the LFM different?

D&G’s model is fundamentally anti-structural. Their “body without organs” is a smooth, un-structured manifold (or “plane of immanence”) upon which desire flows freely until “territorialized” by external forces. The LFM takes the inverse, Lacanian position: the structure is intrinsic. The subject is born into a structured manifold (language, the Other), and the geometry of this manifold is the primary constraint. We retain structure, but we make it dynamic and geometric. [INTERNAL_LINK: Structuralism and post-structuralism -> /pillar/structuralism-vs-post-structuralism].

H2: Synthesis: The Analytic Process as Topological Transformation

The LFM’s final payoff is a new model of the psychoanalytic “cure.”

H3: Classical Analysis: Traversing the Fantasy

In classical Lacanian terms, the “end of analysis” involves “traversing the fundamental fantasy” ($ ⋄ a). This is an act of understanding—of recognizing the fundamental, arbitrary coordinates of one’s desire and, in doing so, gaining a new freedom from them. But what does this “traversing” do?

H3: LFM Interpretation: Flattening Pathological Curvature

The LFM provides a formal answer. The analytic process—specifically, the act of symbolic interpretation—functions as a topological transformation. By “speaking” the unconscious (Freud, 1915c), the analyst and analysand are actively re-weaving the symbolic manifold.

We propose that analysis is analogous to a Ricci flow, a geometric process that systematically smooths out a manifold’s curvature (Perelman, 2002). The “work” of analysis identifies regions of high pathological curvature (fantasy-traps) and, through interpretation, “flattens” them.

H3: Restoring Global Connectivity: A ‘Cured’ Manifold

The “cure” is not the elimination of desire, but the restoration of its global mobility. A “cured” manifold is one with minimal pathological curvature.

On this “flatter” surface, libido (D) is no longer “trapped” in the local minima of jouissance or forced into repressive loops. It can flow globally across the symbolic field, allowing for new, more creative, and less symptomatic symbolic solutions. The subject is “cured” when their desire can flow freely, rather than being dictated by a rigid, inherited geometry. [INTERNAL_LINK: Lacanian psychoanalysis -> /pillar/introduction-to-lacan].

H2: Implications

H3: For Clinical Practice: New Diagnostic Metrics

The LFM moves psychoanalytic diagnosis beyond subjective classification. If Ms is approximated by semantic networks, we can measure a patient’s symbolic rigidity. By analyzing language data from sessions, we could compute the “local semantic curvature” as a concrete diagnostic metric for the rigidity of a subject’s fantasy.

H3: For Computational Psychiatry: Modeling Subjectivity

This model offers a new avenue for computational psychiatry (Montague et al., 2012). It provides a formal physics-based model of subjectivity, rather than a purely cognitive or behavioral one. We can simulate desire flow, test the formation of symptoms as attractors, and model analytic interpretation as a controlled perturbation of the system (Wang & Krystal, 2014).

H3: For Philosophy: A Formalized Subject (Savva, 2025)

The LFM contributes to the philosophical project of formalizing the subject. It models the “subject of the unconscious” ($) not as a static entity, but as a topological-dynamical process. The subject is the geometry of the manifold and the flow of desire across it. This provides a rigorous bridge between post-structuralist philosophy and the mathematical sciences (Savva, 2025).

H2: Conclusion

H3: Summary of the Libidinal Flow Model

The Libidinal Flow Model (LFM) reframes desire as a dynamical process on a geometric background. It posits that the symbolic order is a continuous manifold, that libidinal intensity is a potential field, that desire is the vector field of its flow, and that the fundamental fantasy is the manifold’s intrinsic curvature.

This model resolves the tension between Freud’s “economic” hydrodynamics and Lacan’s “structural” semiotics. It provides a single, unified framework that is both theoretically rigorous and empirically testable.

H3: Future Directions in Topodynamic Psychoanalysis

The LFM is a foundational theory. The immediate next step is empirical verification. This requires a multi-disciplinary effort from psychoanalysts, computational linguists, and physicists. The primary goal is to analyze language data from clinical archives to track changes in semantic network curvature over the course of an analysis. If the LFM’s predictions hold, this would represent a new, quantitative “topodynamic” paradigm for understanding the mind.

H2: End Matter

H3: Assumptions

- The Symbolic-Semantic Equivalence: The LFM assumes that the symbolic manifold (Lacan’s “Other”) is adequately captured, in a geometric sense, by the semantic manifolds generated by NLP models from language data.

- Differentiability of Thought: We assume that the space of signifiers is continuous and “smooth,” allowing the use of differential calculus. This may be a strong simplification.

- Gradient Flow: The model assumes desire follows a simple gradient descent (D

=−∇Φ). The actual dynamics may be more complex, involving non-linear or non-equilibrium processes.

H3: Limits

- Qualia: This is a purely formal, structural model. It describes the dynamics of libido but makes no claim about the qualia of affect—the subjective feeling of desire.

- The Real: The LFM models the Symbolic order. It does not yet have a formal description for the Real (Lacan’s domain of the impossible/traumatic), which may function as a singularity or boundary of the manifold itself.

- Oversimplification: The reduction of “fantasy” to a curvature tensor, while powerful, is a significant simplification of a complex narrative and affective structure.

H3: Testable Predictions

- Prediction 1 (Clinical): Semantic network curvature, computed from a patient’s discourse, will be quantifiably higher (more rigid) in obsessive-compulsive subjects than in “healthy” controls.

- Prediction 2 (Process): Semantic network curvature will contract (i.e., the manifold will “flatten”) during the course of an effective analysis, correlating with symptom reduction.

- Prediction 3 (Neuro-Symbolic): The variance in fMRI signals in associative cortical areas (proxy for Ms) will be inversely correlated with the energy in brainstem affective centers (proxy for Φ), and this relationship will be modulated by the computed curvature of the subject’s semantic network.

H2: References

Amari, S. (2016). Information geometry and its applications. Springer.

Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2018). The entropic brain – revisited. Neuropharmacology, 142, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.03.010

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1980)

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (pp. 4171–4186). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N19-1423

Freud, S. (1915a). Instincts and their vicissitudes. In J. Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 109–140). Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1915c). The unconscious. In J. Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 159–215). Hogarth Press.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

Hatcher, A. (2002). Algebraic topology. Cambridge University Press.

Lacan, J. (1977). Écrits: A selection (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Tavistock Publications. (Original work published 1966)

Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G., & Dean, J. (2013). Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv:1301.3781 [cs.CL]. https://arxiv.org/abs/1301.3781

Montague, P. R., Dolan, R. J., Friston, K. J., & Dayan, P. (2012). Computational psychiatry. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.018

Perelman, G. (2002). The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications. arXiv:math/0211159 [math.DG]. https://arxiv.org/abs/math/0211159

Savva, A. S. (2025). Topology of Symbolic Subjectivity (manuscript). Symbolic Analysis Lab.

Solms, M. (2021). The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. W. W. Norton.

Strogatz, S. H. (2015). Nonlinear dynamics and chaos: With applications to physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering (2nd ed.). Westview Press.

Tu, L. W. (2011). An introduction to manifolds (2nd ed.). Springer.

Wang, X. J., & Krystal, J. H. (2014). Computational psychiatry. Neuron, 84(3), 638–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.018