Introduction: The Flight from Reality to Fantasy

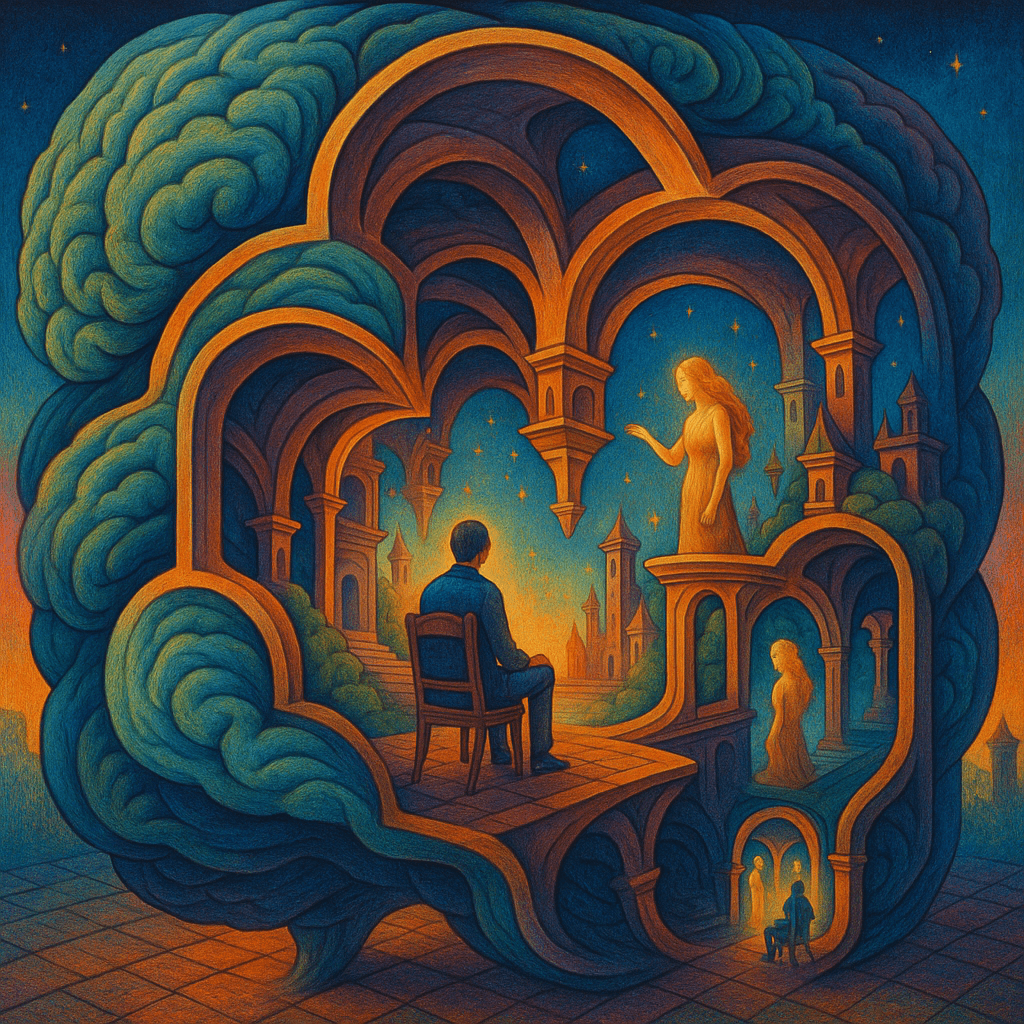

You see someone. A fleeting glance, a brief exchange. An attraction is sparked. But instead of pursuing a connection in the messy, unpredictable real world, something else happens. The mind retreats inward and begins to build. It constructs an elaborate, intricate world—a private theater where this person, now an idealized character, performs perfectly in a script of your own making. This common human experience possesses profound philosophical and psychological depth. What is this mechanism that substitutes a rich, internal fantasy for a risky external reality? It is not merely lust. It is an act of cognitive and emotional architecture, a complex strategy of the self.

To understand it, we must deploy a full analytical toolkit. This essay argues that the retreat into idealized fantasy is a multi-layered strategy that serves defensive, offensive, and avoidant functions. We will explore this phenomenon through four distinct but complementary theoretical lenses. First, we will examine the psychoanalytic blueprint, which frames the fantasy as a defense mechanism managing psychic energy. Second, we will adopt a phenomenological gaze to see it as a tactic for neutralizing the existential threat of the Other. Third, we will consider the existential dilemma, viewing it as a flight from freedom. Finally, we will apply a sociological lens to reveal how these private fantasies are assembled from public, cultural materials.

The Problem: The High-Risk Economy of Real-World Desire

The psyche operates like an economy, seeking to invest its limited psychic energy—a concept Sigmund Freud termed cathexis—in a way that maximizes pleasure and minimizes risk (Freud, 1905). Cathexis is the process of investing mental or emotional energy in a person, object, or idea. When we desire another person, we are making a significant libidinal investment. This investment, however, is fundamentally speculative and occurs in a highly volatile market: reality.

To desire a real person is a high-risk investment. The other person possesses their own agency, their own desires, their own irreducible subjectivity. They can reject, disappoint, or challenge our worldview. This path is fraught with the potential for narcissistic injury, the anxiety of loss, and the painful work of negotiation and compromise. It is a system of high entropy. In contrast, the fantasy offers a perfect hedge. By transferring desire from the real person to an internal image—what psychoanalysis calls an imago—the psyche creates a closed, thermodynamically stable system (Laplanche & Pontalis, 1973). Within this internal world, the self is omnipotent, the idealized other is perfectly compliant, and gratification is guaranteed. The fantasy acts as a powerful regulator, protecting the ego from the volatility of real intersubjective life.

Theoretical Frameworks: Four Lenses on Internal Worlds

No single theory fully captures the architecture of this internal retreat. A rigorous inquiry requires a multi-perspectival approach, integrating insights from psychoanalysis, phenomenology, existentialism, and critical theory.

The Psychoanalytic Blueprint: Desire as a Closed System

The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan provides a structural map for this inner world through his three psychic registers: the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real (Lacan, 2006). Understanding these registers is central to grasping the fantasy’s function. Learn more about Lacan’s three orders.

The Imaginary is the realm of images and ego-identification. The fantasized other is a product of this register. When you place someone “on a pedestal,” you are often projecting your own Ideal Ego—an idealized image of yourself—onto them. They become a mirror reflecting your own unactualized potentials for beauty, wholeness, or freedom (Fink, 1995).

The retreat into fantasy often signals a perceived failure or lack in the Symbolic order—the realm of language, social law, and recognition. If one feels unable to signify their own desirability in the real world’s complex social grammar, they can author a fictional narrative where their value is absolute. The fantasy, therefore, compensates for a Symbolic deficit.

The entire edifice is constructed to foreclose an encounter with the Real—that which resists being captured by image or language. The other person’s true, unpredictable subjectivity is the Real. The fantasy is a meticulously crafted barrier against the anxiety this encounter produces.

The Phenomenological Gaze: Neutralizing the Threat of the Other

Phenomenology asks not “what psychic structure is at play?” but “what is it like to live this fantasy?” Jean-Paul Sartre’s analysis of “The Look” (le regard) is illuminating here (Sartre, 1943). For Sartre, the gaze of another person is an existential threat; it has the power to turn us from a free subject into a determined object in their world, stripping us of our own subjective freedom.

From this perspective, the fantasy is not just a defense mechanism but an offensive strategy. It is a pre-emptive strike to neutralize the other’s threatening freedom by turning them into an object within our world. By making them a character in our story, we master them and escape the anxiety of being perceived, judged, and objectified by a consciousness we cannot control. The fantasy is a reclamation of subjective dominance, a world where our gaze is the only one that matters.

The Existential Dilemma: The Bad Faith of a Pre-Written Script

Existentialism frames this retreat as a flight from the radical freedom and responsibility that define the human condition (Kierkegaard, 1844). To engage with another person is to make a choice, to act in the world, and to be responsible for the consequences. This burden of freedom creates profound anxiety (Angst). Read more on the concepts of freedom and bad faith.

The intricate fantasy is a form of bad faith (mauvaise foi). It is a mode of self-deception where we pretend we are not free (Sartre, 1943). We act as if our fulfillment depends on this perfect, idealized other—an object that exists only in our minds—rather than on the difficult, creative work of building authentic relationships. The fantasy provides a pre-written script, relieving us of the terrifying task of improvising our own lives. It is an abdication of the responsibility that comes with being, in Sartre’s terms, “condemned to be free.”

The Sociological Script: Assembling Fantasy from Cultural Materials

Finally, we must ask to what extent this internal world is truly our own creation. Critical and sociological theory would argue that our fantasies are not spun from nothing; they are assembled from powerful cultural materials (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1944). The “culture industry,” a term coined by Adorno and Horkheimer, produces standardized cultural commodities that shape our desires.

The “perfect woman on a pedestal” is not a purely personal invention. She is often a composite of images and narratives supplied by our culture—from romantic comedies to advertising. Feminist film theory, for example, identifies the “male gaze” as a cinematic convention that structures the visual world around a masculine, objectifying perspective (Mulvey, 1975). This gaze provides a ready-made script for fantasy. Similarly, the construction of woman as the “Other” is a historical and social process, not merely a personal one (de Beauvoir, 1949). The fantasy, then, may not be a retreat from society, but a perfect, frictionless rehearsal of its dominant scripts.

Evidence and Examples: Manifestations in Culture and Life

These theoretical frameworks are not merely abstract. They find concrete expression in both classic literature and contemporary digital life. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby offers a quintessential literary example. Jay Gatsby’s obsession with Daisy Buchanan is not with the real woman but with an idealized imago he constructed years prior, an image that serves as the vessel for his entire identity and ambition (Fitzgerald, 1925). His fantasy is a defense against the trauma of his past and his perceived lack in the Symbolic order of old money.

In the 21st century, these dynamics are amplified by digital technology. The phenomenon of parasocial relationships, where a user forms a one-sided bond with a media figure or online influencer, is a clear example of investing cathexis in a safe, Imaginary object (Giles, 2002). The influencer, curated and presented through a screen, is a perfect object for fantasy—interactive but not truly reciprocal, present but not threateningly Real. This allows for a feeling of connection without the risks of intersubjective engagement.

Objections and Counterarguments: Critiquing the Frameworks

Each of these lenses, while powerful, has its limitations. The psychoanalytic model has been critiqued for its lack of falsifiability; its core tenets are difficult to prove or disprove empirically, operating more like a hermeneutic system than a scientific one (Popper, 1963). Furthermore, it risks pathologizing what might be a normal, even healthy, part of human imagination and creativity. Not all fantasy is a flight from reality; it can also be a rehearsal space for future action.

The existentialist focus on radical individual freedom can be critiqued for understating the power of social and structural constraints. A person’s retreat into fantasy might not be a simple act of “bad faith” but a rational response to oppressive social conditions, economic precarity, or systemic marginalization that make real-world connection genuinely dangerous or impossible (Foucault, 1980). Similarly, the critical theory perspective can verge on determinism, potentially overlooking human agency in interpreting and resisting cultural scripts (Hall, 1980).

Synthesis: A Unified Map of Solitude and Its Price

No single lens offers a complete picture. The retreat into idealized fantasy is a complex human strategy, woven from multiple threads. Explore the foundations of these ideas in Critical Theory.

- It is a psychic defense against the risks of rejection and the anxiety of the Real.

- It is a phenomenological tactic to control the threatening freedom and objectifying gaze of the Other.

- It is an existential flight from the burdensome responsibility of authentic choice.

- It is a cultural script, shaped and reinforced by the media we consume and the societal norms we inhabit.

The central tension remains. The solitary paradise of fantasy offers absolute control, perfect safety, and guaranteed gratification. Its price is sterility. It is a closed loop, incapable of generating anything new, any genuine surprise, or any shared meaning. It is a perfectly preserved past, endlessly replayed. Real human connection, by contrast, is a system of high entropy—unpredictable, risky, and often painful. But it alone holds the possibility of love, recognition, and the creation of a shared future.

Implications: The Developmental and Relational Costs

The persistent preference for fantasy over reality carries significant costs. Developmentally, it can inhibit the growth of emotional resilience. The ego learns and strengthens by navigating the frustrations and disappointments of the real world. By short-circuiting this process, the fantasy fosters a fragile self, ill-equipped to handle the inevitable rejections of life (Baumeister, 1991).

Relationally, this strategy can create a destructive cycle. The idealized imago becomes a benchmark against which all real potential partners are measured and found wanting. This can lead to a chronic inability to form or maintain lasting relationships, as no real person can compete with a perfect, compliant fantasy object (Illouz, 2012). The result is a self-fulfilling prophecy: the world is judged to be disappointing, justifying a further retreat into the more satisfying inner world, which in turn erodes the skills needed to engage with the world.

Conclusion: Choosing the Uncertain Territory

The architecture of idealized fantasy is a testament to the human mind’s creative and defensive powers. It is a fortress built from psychic need, existential dread, and cultural bricks, designed to protect the self from the chaotic beauty of the other. The models from psychoanalysis, existentialism, phenomenology, and critical theory provide a detailed blueprint of this internal construction, revealing its functions and its foundations.

Ultimately, these frameworks converge on a single, vital point. The solitary paradise of fantasy offers a perfect map, but true life can only be found in the uncertain territory. While the retreat inward offers safety, it is the venture outward—into the unpredictable, uncontrollable space between two free subjects—that offers the possibility of growth, meaning, and authentic connection. The choice is between the sterility of a perfect script and the generative chaos of an unwritten life.

Assumptions

- This analysis assumes that the primary goal of the psychic apparatus is to maintain a state of equilibrium and minimize anxiety (psychodynamic assumption).

- It assumes that human consciousness is defined by a fundamental freedom of choice and a corresponding responsibility (existentialist assumption).

- It assumes that individual desires and fantasies are significantly shaped by broader social and cultural forces, not created in a vacuum (sociological assumption).

- It assumes a clear distinction can be made between an “internal” fantasy and “external” reality, though this line can be phenomenologically blurry.

Limits

- This model does not extensively explore the neurobiological underpinnings of fantasy, attachment, and desire, which would offer another level of analysis.

- The frameworks used are primarily derived from Western philosophical and psychological traditions and may not apply universally to all cultural contexts.

- The analysis focuses on the negative or defensive functions of fantasy and spends less time on its potentially positive roles, such as creative inspiration, goal-setting, or psychological rehearsal for future events.

- The discussion is largely theoretical and does not incorporate empirical data from clinical psychology or sociology to test the claims made.

Testable Predictions

- Prediction 1: Individuals scoring higher on validated measures of neuroticism and rejection sensitivity will report a greater frequency and intensity of idealized romantic fantasizing following a novel social encounter.

- Prediction 2: A longitudinal study would show that individuals who predominantly engage in idealized fantasy will report lower relationship satisfaction and shorter relationship durations compared to a control group, even when controlling for other personality factors.

- Prediction 3: An experimental study exposing one group to highly idealized romantic media (e.g., romantic comedies) and a control group to neutral media would find that the first group subsequently rates the profiles of average potential partners on a dating app more negatively.

References

Adorno, T. W., & Horkheimer, M. (1944). Dialectic of Enlightenment. Social Studies Association, Inc.

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Escaping the self: Alcoholism, spirituality, masochism, and other flights from the burden of selfhood. Basic Books.

de Beauvoir, S. (1949). The Second Sex. (H. M. Parshley, Trans.). Vintage Books. (Original work published 1949)

Fink, B. (1995). The Lacanian subject: Between language and jouissance. Princeton University Press.

Fitzgerald, F. S. (1925). The Great Gatsby. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. (C. Gordon, Ed.). Pantheon Books.

Freud, S. (1962). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In J. Strachey (Ed. and Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 123-245). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1905)

Giles, D. C. (2002). Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology, 4(3), 279–305. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0403_01

Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/Decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, media, language: Working papers in cultural studies, 1972-79 (pp. 128-138). Hutchinson.

Illouz, E. (2012). Why love hurts: A sociological explanation. Polity Press.

Kierkegaard, S. (1980). The concept of anxiety: A simple psychologically orienting deliberation on the dogmatic issue of hereditary sin. (R. Thomte & A. B. Anderson, Ed. and Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1844)

Lacan, J. (2006). Écrits: The first complete edition in English. (B. Fink, Trans.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Laplanche, J., & Pontalis, J.-B. (1973). The language of psycho-analysis. (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

Popper, K. R. (1963). Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Sartre, J.-P. (1956). Being and nothingness: An essay on phenomenological ontology. (H. E. Barnes, Trans.). Philosophical Library. (Original work published 1943)