Introduction

The Central Claim: From Libido to Control Architecture

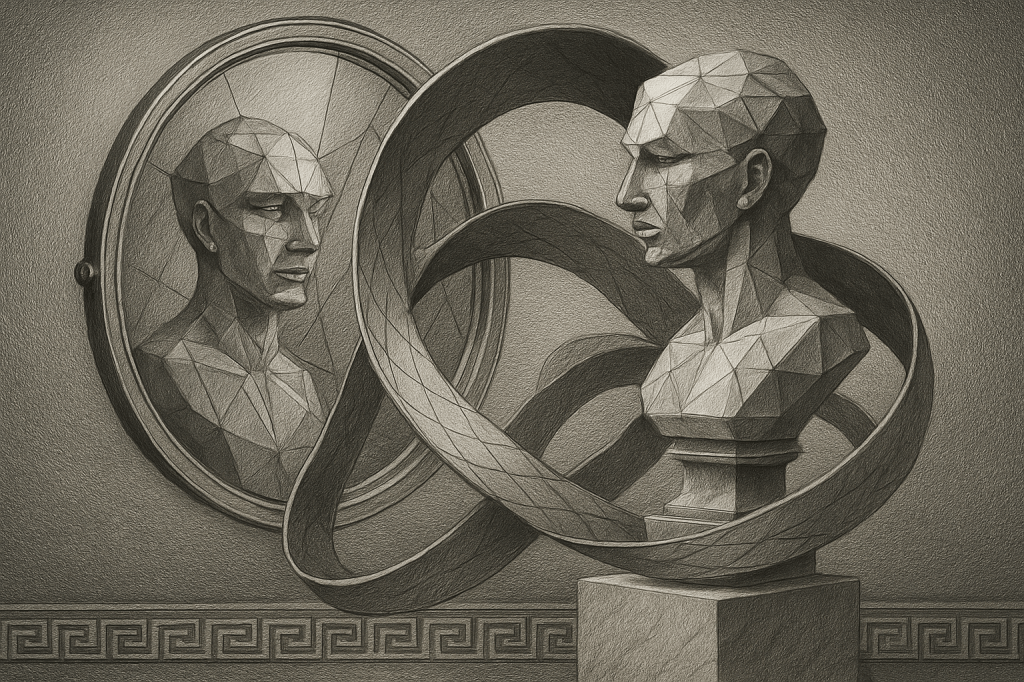

Many subjects construct intricate, persistent erotic narratives around minimally known others. A brief encounter or a fleeting image can become the seed for an entire world, meticulously curated within the subject’s mind. In this internal theater, the other is elevated, their complexities and contradictions pruned away, and the scene unfolds according to rules the subject alone controls. The central claim of this essay is that such fantasy is not a mere excess of libido but a sophisticated libidinal control architecture. It functions as a risk-control policy that systematically trades the uncertainty of interpersonal encounter for the coherence of a simulation. It achieves this by displacing cathexis from the living person to an idealized representation, thereby simulating reciprocity without the disruptive presence of true alterity.

Defining Key Terms: Fantasy, Recognition, and Alterity

Before proceeding, we must define three key terms. Fantasy, in this context, refers to a structured, repeatable, and often compulsive imaginal scenario, distinct from transient daydreaming. Recognition follows the Hegelian tradition, denoting the process by which a subject’s self-consciousness is affirmed through the acknowledgment of another free, independent subject; it is a mutual, contingent process (Honneth, 1995). Alterity refers to the state of “otherness”—the irreducible, unpredictable, and uncontrollable quality of another subject who possesses their own desires and agency, which may not align with one’s own. This model posits that compulsive fantasy maximizes gratification by eliminating alterity, which in turn makes genuine recognition impossible.

Article Roadmap

This essay will unfold in a structured manner. First, it will frame the core problem: the high-variance cost of authentic interpersonal engagement. Second, it will present a multi-layered theoretical framework integrating psychoanalytic structure, a risk-sensitive control model, predictive processing, and the philosophical constraint of recognition. Third, it will ground this theory in clinical and empirical examples. Fourth, it will address key objections. Finally, it will synthesize these elements to propose actionable clinical and ethical corollaries, concluding with a set of testable predictions derived from the formal model.

The Problem: The High-Variance Cost of Reciprocity

Quantifying the Risks: Rejection, Shame, and Dependency

Live interaction with a desired other is an inherently high-variance undertaking. The potential outcomes are widely distributed, ranging from profound attunement to acute rejection. The “cost” of a negative outcome is not trivial; it can manifest as shame, a perceived loss of social standing, or a painful sense of dependency on the other’s validation (Leary, 2015). Neurobiological evidence suggests that the pain of social rejection is processed in brain regions overlapping with those that process physical pain (Eisenberger, 2012). These potential negative outcomes constitute the risk—or statistical variance—that a subject must be willing to bear. For individuals with a low tolerance for this variance, the psychic cost of potential failure can loom larger than the potential reward of success.

The Subject’s Dilemma: Predictable Gratification vs. Uncertain Recognition

This sets up a fundamental choice. On one hand is the path of authentic engagement, which offers the possibility of genuine recognition but carries the significant risk of rejection and psychic pain. On the other hand is the path of fantasy, which offers guaranteed gratification within a closed, predictable system. The imaginal scenario is constructed to have near-zero variance; the outcome is known and optimized in advance. The dilemma, therefore, is not simply between pleasure and displeasure, but between a high-risk, high-reward strategy (reciprocity) and a low-risk, guaranteed-reward strategy (fantasy). An internal cognitive risk-management framework is implicitly deployed to make this choice.

Theory: A Multi-Layered Control Framework

To fully capture this dynamic, a single theoretical lens is insufficient. We must integrate insights from psychoanalysis, control theory, and cognitive science.

The Psychoanalytic Structure: Imaginary, Symbolic, and the Drive

Following Lacanian theory, an encounter with an other can be mapped onto three registers (Lacan, 2006). First is the Imaginary: the pre-linguistic realm of images and identifications, where the subject forms an idealized image of the other. Second is the Symbolic: the realm of language, social norms, and cultural scripts that give structure and narrative form to the fantasy. The “pedestalization” operator works here, projecting the Imaginary image onto a purified Symbolic ideal. Third is the Real: the unsymbolizable remainder of raw drive that resists complete description. Compulsive fantasy attempts to manage this drive by binding it entirely within the Imaginary-Symbolic circuit, preventing the disruptive eruption of the Real that authentic encounter entails. This aligns with foundational psychoanalytic frameworks of mental functioning.

The Risk-Sensitive Policy Model of Choice

We can formalize the subject’s dilemma using a risk-sensitive policy model (Carver & Scheier, 1982). The subject chooses fantasy over a real encounter when the utility of fantasy outweighs the risk-adjusted utility of the real. In a compact form:

Select fantasy if: $U_{fant} > E[U_{real}] – \lambda \cdot \text{Var}(L_{real})$

Where:

- $U_{fant}$ is the high, predictable utility of the fantasy scenario.

- $E[U_{real}]$ is the expected utility of a real encounter.

- $L_{real}$ represents the potential “loss” from a real encounter, defined as a weighted sum of negative outcomes: $L_{real} = \alpha \cdot \text{Rejection} + \beta \cdot \text{Shame} + \gamma \cdot \text{Dependency} – \delta \cdot \text{Attunement} + \text{noise}$.

- $\text{Var}(L_{real})$ is the variance of that potential loss—the measure of risk and unpredictability.

- $\lambda$ (lambda) is the coefficient of risk sensitivity, or variance aversion. A higher $\lambda$ indicates a greater aversion to uncertainty.

By its construction, the variance of loss in fantasy, $\text{Var}(L_{fant})$, is approximately zero. As a subject’s risk aversion ($\lambda$) increases, or as past negative experiences inflate the perceived variance of real encounters, the policy will increasingly shift toward fantasy.

The Predictive-Processing Bridge: Minimizing Surprise

This model aligns neatly with contemporary theories of the brain as a “prediction machine” (Clark, 2013). Under predictive coding frameworks, organisms seek to minimize “surprise,” or the delta between their predictions and sensory inputs. An open-ended interaction with another subject is rife with potential surprise. Fantasy, conversely, is an environment of radical predictability. The subject authors the script, plays all the parts, and ensures the outcome aligns perfectly with their priors. This low-entropy, low-surprise state is intrinsically rewarding to a predictive system, even if it sacrifices the informational richness and growth that comes from genuine surprise.

The Recognition Constraint: Hegel’s Master-Slave Dialectic in Desire

The model’s primary cost is incurred here. Desire is not merely for pleasure but for recognition by another consciousness (Hegel, 1977). This requires a struggle in which one’s own subjectivity is risked and, ideally, returned and affirmed by the other. Pedestalization short-circuits this process. The fantasizing subject is not engaging with an other but with a curated reflection of their own ideal. The gratification is high, but it is the gratification of self-reflection, not mutual recognition. Over time, this trades the vitality of being seen by another for the sterile control of authoring how one is seen. This dynamic is a core component in the modern theory of recognition.

Evidence and Examples

Clinical Vignettes: Avoidant and Narcissistic Presentations

This model finds grounding in clinical observation. For instance, subjects with avoidant personality structures often report elaborate inner worlds where relationships are perfect and safe, a stark contrast to their sparse real-world social engagement (Meyer & Ajchenbrenner, 2008). The high $\lambda$ (risk sensitivity) is a core feature of their presentation. Conversely, in narcissistic structures, fantasy can serve to uphold a grandiose self-image, with the imaginal other existing purely to provide adoration without the risk of dissent or independent desire (Ronningstam, 2011; Kernberg, 1975).

Empirical Proxies: Data from Attachment and Behavioral Studies

While direct measurement of fantasy is difficult, empirical proxies lend support to the model. Studies on attachment theory show that individuals with insecure attachment styles, often stemming from unpredictable caregiving, exhibit a lower tolerance for interpersonal uncertainty in adulthood (Bowlby, 1969; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Furthermore, behavioral economics experiments consistently demonstrate that many individuals are variance-averse, preferring a smaller, certain reward over a larger, uncertain one, a principle that maps directly onto the choice between fantasy and reality (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979).

Literary Archetypes: From Petrarch to Modern Fiction

This dynamic is not new; it is a foundational theme in literature. Petrarch’s sonnets to the idealized, distant Laura established a template for a love that thrives on absence and idealization (Mazzotta, 1993). The object of desire is more potent as a catalyst for internal poetry than as a living interlocutor. This archetype persists in modern narratives where protagonists engage more deeply with their idea of a person than with the person themselves, a dynamic often leading to tragic or hollow outcomes when fantasy confronts reality, as exemplified by Jay Gatsby’s idealized conception of Daisy Buchanan (Tredell, 2007).

Objections and Counterarguments

The “Harmless Escapism” Objection

A common objection is that such fantasy is simply benign, harmless escapism. The model does not dispute the regulatory function of fantasy. However, it refutes the “harmless” designation by positing a specific, measurable cost: a long-run deficit in recognition that corrodes vitality and the capacity for growth. While episodically rewarding, a chronic policy of fantasy leads to a static, closed-loop existence. This is a crucial distinction from a prior post exploring healthy escapism vs dissociation.

Alternative Explanations: Simple Operant Conditioning

A more parsimonious explanation might be simple operant conditioning. Fantasy provides a pleasurable stimulus (positive reinforcement), while avoiding real interaction removes a potential threat (negative reinforcement). This is true, but it is an incomplete account. A behaviorist model cannot explain the complex structure of fantasy, its reliance on cultural scripts, the role of idealization, or the qualitative difference between pleasure and recognition (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). It describes the “what” of the reinforcement loop but not the “how” or the “why.”

The Limits of Formalism in Describing Subjectivity

Finally, any formal model of a subjective, phenomenological experience faces a valid philosophical challenge. Can a utility function and a variance term truly capture the lived experience of desire and fear? The model does not claim to be a perfect representation of subjectivity. Rather, it is an “as-if” model—it proposes that the subject’s behavior can be described as if they were solving this equation. Its value lies not in perfectly mapping consciousness, but in generating a coherent structure and a set of falsifiable predictions.

Synthesis: Reconciling Control with Vitality

Dysfunction as a Threshold, Not a Category

The model treats the function of fantasy as adaptive risk regulation. It becomes dysfunctional only when it crosses a critical threshold—when the avoidance of variance leads to the decay of all approach behaviors and recognition falls below a level necessary for psychic viability. It is a dimensional, not a categorical, issue. Everyone engages in fantasy; the pathology lies in the chronic, compulsive foreclosure of any alternative strategy.

The Role of Mimetic Desire in Inflating Idealization

The process is not entirely internal. As René Girard argued, desire is often mimetic—we desire what others desire (Girard, 1965). Pedestalization can be powerfully amplified by perceived third-party valuation. The other is idealized not just for their intrinsic qualities, but because they are seen as a high-value object within a social field. This mimetic gradient inflates their perceived value, widens the gap between the ideal and the real, and tightens the compulsive loop. For more on this, see our pillar page on mimetic desire and modern life.

Creativity vs. Compulsion: The Permeable Boundary

Finally, a distinction must be made between compulsive and creative fantasy. Creative fantasy, as described by Winnicott’s concept of transitional phenomena, exists in a permeable space between self and other (Winnicott, 1971). It is open to revision and correction by encounter with reality. Compulsive fantasy is closed and rigid. It actively refuses disconfirmation. The former supports growth and art; the latter drifts toward sterile control.

Implications: Clinical and Ethical Corollaries

Therapeutic Interventions: From Naming the Function to Entropy Training

The model suggests several clinical pathways. First, name the function: re-frame the fantasy not as a moral failing or a symptom of excessive lust, but as a variance-control strategy. Making the function explicit can weaken the compulsion. Second, implement entropy training: use graded, low-stakes micro-bids for connection (e.g., brief, low-expectation interactions) to systematically lower variance aversion ($\lambda$) and rebuild tolerance for uncertainty. Third, practice de-idealization rituals: deliberately introduce narrative “noise” or imperfections into the fantasy to reduce its gain and preserve the other’s opacity.

Conclusion

Summary of the Model

We have proposed a model wherein persistent sexualized fantasy functions as a risk-control policy. It re-anchors desire from a living other to an idealized signifier and runs low-entropy simulations to guarantee gratification. This strategy, while effective at managing the perceived risks of rejection and shame, comes at the cost of genuine recognition, which is essential for long-term psychic vitality. By integrating psychoanalytic, control-theoretic, and philosophical concepts, this framework provides a robust explanation for the compulsive nature of such fantasies and offers a clear logic for intervention.

Future Directions for Research

Future research should focus on operationalizing the key variables in this model. Developing and validating scales for “narrative closure,” risk sensitivity in social domains ($\lambda$), and perceived recognition could allow for empirical testing of the model’s core propositions. Neuroimaging studies could investigate whether fantasy-related neural circuits overlap with those involved in risk assessment and model-based decision-making. Such work would move the discussion from pure theory to testable science. Another avenue is explored in our post on the neuroscience of social cognition.

End Matter

Assumptions

- This model assumes that human decision-making, even in the libidinal realm, can be productively modeled as if it were optimizing a risk-adjusted utility function.

- It assumes a psychic apparatus structured by Imaginary and Symbolic registers, consistent with a broadly psychoanalytic framework.

- It assumes that “recognition” is a fundamental human need, distinct from and not reducible to pleasure or gratification.

Limits

- The model is primarily descriptive and conceptual; it does not specify the precise quantitative values for its parameters (e.g., $\lambda$, $\alpha$, $\beta$) which would likely vary significantly across individuals.

- It does not fully account for the neurobiological substrates of fantasy, attachment, and risk aversion, though it is compatible with such findings.

- The model risks over-rationalizing a process that is often experienced as involuntary and ego-dystonic.

Testable Predictions

- Displacement Hypothesis: An experimentally induced increase in the perceived variance of social feedback will lead to a measurable increase in self-reported time spent in intentional fantasy episodes.

- Coherence Filter Hypothesis: Subjects who score higher on measures of compulsivity will describe the objects of their fantasies with fewer contradictory or “messy” attributes compared to control subjects.

- Recognition Deficit Hypothesis: Longitudinal studies will show that while fantasy load may correlate positively with short-term mood regulation, it will correlate negatively with long-term measures of life satisfaction and interpersonal connectedness.

- Cost Inflation Hypothesis: A higher “idealization score” for a fantasy object will predict lower real-world approach behavior toward potential partners.

References

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Attachment and Loss.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1982). Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 92(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.92.1.111

Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1200047X

Eisenberger, N. I. (2012). The painful social self: A social cognitive neuroscience approach to rejection. In J. Decety & J. T. Cacioppo (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of social neuroscience (pp. 495–510). Oxford University Press.

Girard, R. (1965). Deceit, desire, and the novel: Self and other in literary structure (Y. Freccero, Trans.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hegel, G. W. F. (1977). Phenomenology of spirit (A. V. Miller, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

Honneth, A. (1995). The struggle for recognition: The moral grammar of social conflicts (J. Anderson, Trans.). MIT Press.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Kernberg, O. F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. Jason Aronson.

Lacan, J. (2006). Écrits: The first complete edition in English (B. Fink, Trans.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Leary, M. R. (2015). Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(4), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.4/mleary

Mazzotta, G. (1993). The worlds of Petrarch. Duke University Press.

Meyer, B., & Ajchenbrenner, M. (2008). The internal world of the avoider: A psychodynamic and attachment perspective on avoidant personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 15(3), 263-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2007.12.007

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Ronningstam, E. (2011). Narcissistic personality disorder in DSM-V–in support of retaining a significant diagnosis. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(1), 28-40. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2011.25.1.28

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. Guilford Press.

Tredell, N. (2007). Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Continuum.

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. Routledge.