1. Introduction: The Fiction of Interchangeability

1.1 The Case of λευκό and άσπρο

Language presents us with an illusion of simplicity. We operate under the convenient fiction that a word can be substituted for another without loss or alteration of meaning. This is the concept of the synonym, a cornerstone of lexicography. Yet, upon rigorous inspection, this concept dissolves. Consider the Modern Greek words λευκό (leukó) and άσπρο (áspro). Both denote the color “white.” A dictionary might list them as synonyms, and for many practical purposes, they are interchangeable. However, to a native speaker, they are profoundly different. Λευκό, with its roots in ancient Greek (λευκός), carries the formal, scientific, and classical register of leukocytes (λευκοκύτταρα) and the White House (Λευκός Οίκος). Άσπρο, from a medieval root (ἄσπρος), is the vernacular, everyday “white.” The choice of word does not merely point to a color; it invokes a world, a specific linguistic and cultural frame (Geeraerts, 2010).

1.2 Quine’s Ghost and the Collapse of Analyticity

This intuitive sense of non-identity was given its most formidable philosophical grounding by Willard Van Orman Quine in his seminal 1951 paper, “Two Dogmas of Empiricism.” Quine’s target was the long-held distinction between analytic truths (true by meaning alone, e.g., “All bachelors are unmarried men”) and synthetic truths (true by fact). The distinction depended entirely on a coherent notion of “synonymy.” Quine demonstrated that any attempt to define synonymy without circularity was doomed. One cannot define synonymy through interchangeability in all contexts salva veritate without presupposing a concept of “necessity” or “analyticity” to begin with (Quine, 1951). The argument was devastating: if we cannot give a non-circular account of “sameness of meaning,” the entire edifice of analyticity, a central pillar of logical positivism, collapses. This left philosophy with a holistic view of language as a “web of belief,” where statements are confirmed or disconfirmed not in isolation but as part of a larger system (Putnam, 1975b). For a deeper dive, see our previous post on Quine’s critique of analyticity.

1.3 The Analogical Thesis

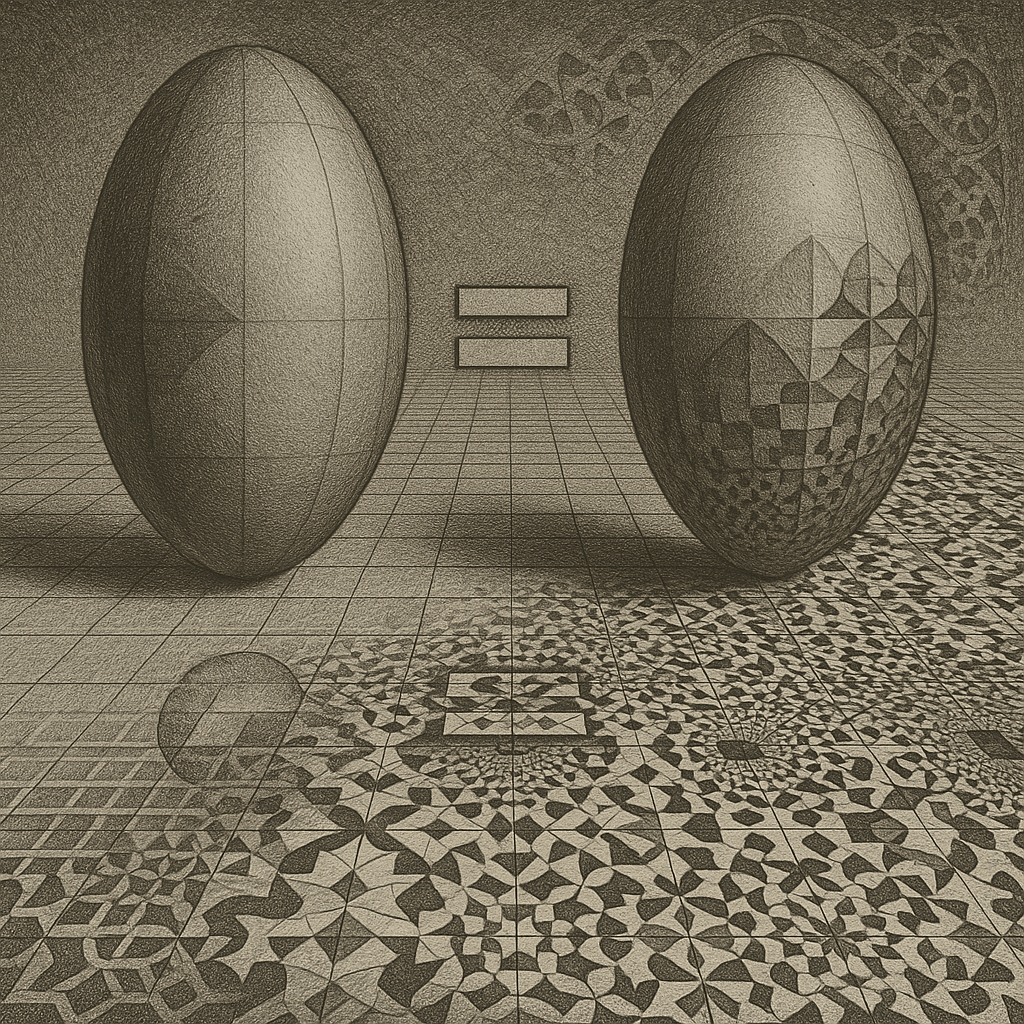

Quine’s deconstruction of synonymy provides a powerful lens for examining other domains where signs relate to objects. This paper’s central thesis is that the granular, context-dependent, and non-interchangeable nature of so-called “synonyms” in natural language provides a robust framework for re-evaluating the relationship between abstract objects and their varied representations in mathematics. Just as λευκό and άσπρο are not merely different labels for the same color concept but are different ways of constituting that concept within a discourse, so too are different mathematical formalisms not simply interchangeable names for a pre-existing Platonic object. The choice of representation is a choice of a conceptual world, complete with its own affordances, limitations, and pathways of discovery. Equivalence, in mathematics as in language, does not imply identity of meaning or conceptual function.

2. The Problem: Deconstructing “Sameness of Meaning”

2.1 Goodman’s Extensional Test for Non-Synonymy

While Quine demonstrated the circularity of defining synonymy, Nelson Goodman, in his 1949 paper “On Likeness of Meaning,” offered a more concrete, extensional test. An extension of a term is the set of all things to which that term applies. Goodman noted that co-extensionality is a necessary but insufficient condition for synonymy. His famous counterexample was “centaur” and “unicorn.” Both have the same primary extension—the null set. Yet, they clearly do not mean the same thing. To solve this, Goodman introduced the concept of secondary extensions. The meaning of a word includes not only its own extension but also the extensions of all compound terms that can be formed from it. While there are no centaurs or unicorns, there are “pictures of a centaur” and “pictures of a unicorn,” and these sets are not co-extensive. Therefore, “centaur” and “unicorn” are not synonyms (Goodman, 1949). This framework provides a formal basis for our intuitive distinction between λευκό and άσπρο. The compound term λευκοκύτταρο (leukocyte) is a core biological term, while ασπροκύτταρο is nonsensical, proving their non-synonymy.

2.2 Putnam and the Social Dimension of Meaning

Hilary Putnam further complicated the picture by arguing that meaning is not something located purely in the head of any individual speaker. In his famous “Twin Earth” thought experiment, he argued that “meanings just ain’t in the head” (Putnam, 1975a). The reference of a term like “water” is fixed by its underlying chemical structure (H₂O), a structure that speakers may not know but which is known by experts. This creates a “division of linguistic labor.” The full meaning of a term is a property of the linguistic community as a whole. This social dimension makes perfect synonymy even more intractable. For two words to be synonymous, they would have to be embedded in the socio-linguistic structure of the community in precisely the same way, a condition that is virtually impossible to meet. This externalist view of meaning is central to the modern philosophy of language.

2.3 Cognitive Linguistics and the Principle of Contrast

Twentieth-century linguistics moved beyond purely logical and referential theories to incorporate cognitive and pragmatic factors. Thinkers like D. A. Cruse (1986) argued that natural languages actively “abhor” true synonyms due to the Principle of Contrast: the assumption that any difference in linguistic form corresponds to a difference in meaning. From a pragmatic perspective, having two perfectly interchangeable words is inefficient; pressures of communication force them to specialize in register, connotation, or context (Clark, 1987). Cognitive linguistics, particularly the work of George Lakoff, further argues that meaning is embodied and grounded in metaphorical structures (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). From this perspective, λευκό and άσπρο activate different cognitive networks or “frames” (Fillmore, 1982). They are not two pointers to one “white” concept; they are two different ways of experiencing and conceptualizing whiteness.

3. The Theory: Representation as a Constitutive Act

3.1 The Mathematical Analogue

The principles of non-identical equivalence and the constitutive power of form, so clearly visible in language, apply with equal force in mathematics. A representation in this context refers to a system of signs, definitions, and operational rules used to express a mathematical object or structure (e.g., fractional notation, Cartesian coordinates). A formalism is a highly developed representational system (e.g., Lagrangian mechanics). The central theory of this post is that these representations are not neutral acts of labeling a pre-existing, transcendent object. They are acts of constitution.

3.2 Representation vs. Description

The core of the argument rests on a distinction between description and constitution. A descriptive label, like a price tag, can be swapped with another of equal value without changing the nature of the object it is attached to. A constitutive representation, however, is like a legal framework; it actively shapes and defines the properties and potential actions related to the object. Changing the representation changes the conceptual object itself by altering its connections, its operational affordances, and the intellectual pathways it opens. Mathematical discovery is therefore not merely the uncovering of pre-existing facts but is often the invention of powerful new constitutive representations.

4. Evidence: Case Studies in Mathematics and Physics

4.1 Case Study: The Natures of Number (1/2 vs. 0.5; Dedekind vs. Cantor)

The distinction between $1/2$ and $0.5$ is a microcosm of this issue. Both denote the same rational number. However, the fractional representation $1/2$ foregrounds a relationship of partition and ratio, living naturally in the algebraic world of rings and fields. The decimal representation $0.5$ situates the number on a continuous number line within a base-10 positional system, prioritizing approximation and measurement. This divergence becomes clearer when constructing the real numbers. Richard Dedekind’s method of cuts (a partition of rationals) and Georg Cantor’s method (equivalence classes of Cauchy sequences) both construct isomorphic, complete ordered fields. Yet, a Dedekind cut is a static, set-theoretic object, while a Cauchy sequence is a dynamic, procedural, analytic object. Their “secondary extensions”—the types of proofs and ideas they inspire—are different (Corry, 2004). They are not synonymous definitions but different constructions of the mathematical continuum.

4.2 Case Study: The Worlds of Geometry (Euclidean vs. Cartesian)

For over two millennia, Euclidean geometry was the science of space, using an axiomatic, synthetic method based on visual intuition. The invention of Cartesian geometry by René Descartes, associating points with coordinates, translated geometry into algebra. While both describe the same flat, three-dimensional space, they are not synonymous. The algebraic form invites calculation, transformation, and generalization to higher dimensions in a way the purely geometric form does not (Grosholz, 2007). They are not two labels for “space”; they are two fundamentally different formal systems for constituting and exploring the concept of space.

4.3 Case Study: The Languages of Physics (Lagrangian vs. Hamiltonian)

This principle extends into theoretical physics. In classical mechanics, Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics produce identical equations of motion. However, Lagrangian mechanics, based on the principle of least action, offers a holistic, global perspective. Hamiltonian mechanics, based on phase space, offers a local, differential perspective. The Hamiltonian formalism was the essential language for the transition to quantum mechanics. Conversely, the Lagrangian formalism is the natural starting point for modern quantum field theory and the path integral formulation (Feynman, 1948). To treat them as synonyms would be to miss that they are distinct conceptual engines, each driving progress in different directions (Butterfield, 2004).

5. Objections: The Platonist and Structuralist Positions

5.1 The Gödelian Platonist Challenge

The thesis that representation is constitutive faces a significant challenge from Gödelian Platonism. This view, advanced by Kurt Gödel, holds that mathematical objects exist independently in an abstract realm, which mathematicians perceive through a form of intuition (Gödel, 1964). For a Platonist, different definitions for the real numbers are simply different descriptions of the same independently existing objects. The fact that Dedekind’s and Cantor’s constructions are isomorphic is powerful evidence that they have both successfully “found” the one true set of real numbers. This view relegates representation to a secondary, descriptive role. However, it struggles to account for why a mere change in description should open up entire fields of inquiry that another leaves obscured. The history of mathematics suggests the “description” is doing much of the conceptual work (Shapiro, 2000).

5.2 The Structuralist Rebuttal and Its Limits

In contrast, Structuralism holds that mathematics is the study of structures, not objects. A mathematical “object” is defined purely by its relations to other objects within a structure (Resnik, 1997; Shapiro, 1997). This elegantly handles multiple representations—they are all just instances (instantiations) of the same abstract structure. However, this view tends to efface the very real cognitive and practical differences between these instances. Our linguistic analogy suggests a refinement: while different formalisms may instantiate the same abstract structure, they are not conceptually identical. They are different “languages” for describing that structure, and each language has its own grammar and power. The debate between these positions is a core topic in the modern philosophy of mathematics. See our overview of Platonism versus Structuralism.

6. Synthesis: Beyond Labels to Conceptual Worlds

6.1 Unifying the Linguistic and Formal Arguments

The journey from the linguistic distinction between λευκό and άσπρο to the conceptual divergence of Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics reveals a single, powerful principle: representational systems are not passive labels. They are cognitive toolkits. The Platonist view correctly intuits that there is a common “thing” being captured, while the Structuralist view correctly identifies this “thing” as a structure. However, both views underestimate the role of the representation itself. The act of representation is an act of constitution. The choice of a word or a formalism is a choice of a cognitive framework, one that brings certain features of the world into focus while leaving others in the background (Goodman, 1976).

6.2 From Shades of Meaning to Shades of Being

The difference between λευκό and άσπρο is not just a difference in connotation; it is a difference in the reality being invoked—a scientific reality versus a vernacular one. It is a difference in being. Similarly, the difference between defining a real number as a Dedekind cut versus a Cauchy sequence is a difference in how the very being of the mathematical continuum is constructed. These are not merely shades of meaning, but shades of being. The representation breathes life into the abstract structure in a particular way, giving it a specific “mode of existence” in our conceptual scheme.

7. Implications: The Generative Power of Plurality

7.1 For the Philosophy of Mathematics and Language

This perspective has significant implications. For the philosophy of language, it reinforces a functional, pragmatic, and cognitively grounded view of meaning. For the philosophy of mathematics, it argues against a naive Platonism. The mathematician is not a passive observer of a transcendent realm; he or she is an active creator of conceptual structures. The invention of a new formalism can be as profound a discovery as the proof of a new theorem (Thurston, 1994). It suggests that mathematical reality is not found, but made.

7.2 For Scientific and Mathematical Practice

This understanding has practical consequences. It encourages the exploration of multiple, equivalent formalisms for the same problem, recognizing that each may unlock different insights. It validates the difficult, creative work of developing new notation and representation, placing it on par with theorem-proving. For scientists and mathematicians, it serves as a reminder that the language we choose to describe reality actively shapes what we are capable of discovering within it.

8. Conclusion

The search for perfect synonyms, for a single true name for a thing, is ultimately a misguided quest. It is a search for a kind of certainty and simplicity that reality—whether linguistic, mathematical, or physical—does not afford. The richness of human thought, from the poetic nuances of everyday speech to the elegant architecture of mathematical physics, lies not in a sterile equivalence of signs, but in the generative and irreducible plurality of its representations.

End Matter

Assumptions

- This argument assumes that the analogy between signs in natural language and representational systems in formal sciences is conceptually valid and illuminating.

- It assumes a functionalist perspective, where the “meaning” of a representation is determined by its use and conceptual affordances, not solely by its referent.

- It presupposes that cognitive and pragmatic factors are relevant to the analysis of formal systems, not just linguistic ones.

Limits

- The analysis is limited to a small number of illustrative case studies and does not constitute an exhaustive proof.

- It does not deeply engage with nominalist objections (e.g., Azzouni, 2004) that deny the existence of abstract objects altogether.

- The argument focuses on referential and structural representations, and may not apply equally well to non-referential or purely aesthetic uses of language and symbols.

Testable Predictions

- In Formal Systems: If a long-standing mathematical or physical problem is successfully approached with a radically new formalism, that new formalism will generate a distinct set of new research questions and applications that were not apparent from within the old formalism.

- In Linguistics: If a community coins or borrows a new term that is, at outset, extensionally identical to an existing term, the two terms will rapidly diverge in register, connotation, or context of use to avoid redundancy, following the Principle of Contrast.

- In Cognitive Science: When solving problems, experts who are fluent in two equivalent formalisms (e.g., Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics) should exhibit different patterns of neural activation or problem-solving strategies depending on which formalism is cued, even if the problem’s underlying structure is identical.

References

Azzouni, J. (2004). Deflating Existential Consequence: A Case for Nominalism. Oxford University Press.

Benacerraf, P. (1965). What Numbers Could Not Be. The Philosophical Review, 74(1), 47–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183530

Butterfield, J. (2004). On the Equivalence of Theories. In Philosophy of Physics (pp. 915-965). Elsevier.

Carnap, R. (1937). The Logical Syntax of Language. Kegan Paul.

Clark, E. V. (1987). The Principle of Contrast: A Constraint on Language Acquisition. In B. MacWhinney (Ed.), Mechanisms of Language Acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Corry, L. (2004). Modern Algebra and the Rise of Mathematical Structures. Birkhäuser.

Cruse, D. A. (1986). Lexical Semantics. Cambridge University Press.

Dummett, M. (1991). Frege: Philosophy of Mathematics. Harvard University Press.

Feynman, R. P. (1948). Space-Time Approach to Non-Relativistic Quantum Mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics, 20(2), 367–387. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.20.367

Fillmore, C. J. (1982). Frame Semantics. In Linguistics in the Morning Calm. Hanshin Publishing Co.

Geeraerts, D. (2010). Theories of Lexical Semantics. Oxford University Press.

Gödel, K. (1964). What is Cantor’s Continuum Problem? In P. Benacerraf & H. Putnam (Eds.), Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings. Cambridge University Press.

Goodman, N. (1949). On Likeness of Meaning. Analysis, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/3326585

Goodman, N. (1976). Languages of Art. Hackett Publishing.

Grosholz, E. R. (2007). Representation and Productive Ambiguity in Mathematics and the Sciences. Oxford University Press.

Hellman, G. (1989). Mathematics Without Numbers: Towards a Modal-Structural Interpretation. Oxford University Press.

Kripke, S. A. (1980). Naming and Necessity. Harvard University Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press.

Maddy, P. (1997). Naturalism in Mathematics. Oxford University Press.

Putnam, H. (1975a). The Meaning of ‘Meaning’. In Mind, Language, and Reality. Cambridge University Press.

Putnam, H. (1975b). The Analytic and the Synthetic. In Mind, Language, and Reality. Cambridge University Press.

Quine, W. V. O. (1951). Two Dogmas of Empiricism. The Philosophical Review, 60(1), 20–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/2181906

Resnik, M. D. (1997). Mathematics as a Science of Patterns. Oxford University Press.

Shapiro, S. (1997). Philosophy of Mathematics: Structure and Ontology. Oxford University Press.

Shapiro, S. (2000). Thinking about Mathematics: The Philosophy of Mathematics. Oxford University Press.

Thurston, W. P. (1994). On Proof and Progress in Mathematics. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 30(2), 161-177. https://doi.org/10.1090/S0273-0979-1994-00502-6